STORY BY SARAH FULTON

Female faculty at Drake University are making up to 12 percent less on average than their male colleagues.

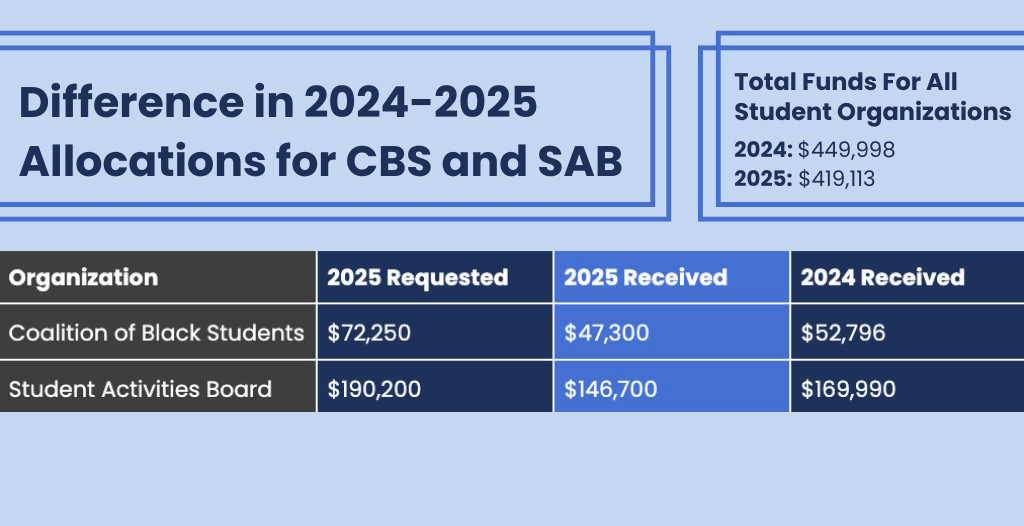

The 2012-2013 data provided by Drake to the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) shows that the average wage discrepancy increases as women move up in the ranks. Assistant professors are paid four percent less, amounting to a difference of around $400. Associate professors make 11 percent less, a difference of $2,500. Full-time professors make 12 percent less for a yearly difference of $13,500.

“I am not saying that there is a nefarious intent there but the outcome is real,” sociology professor Darcie Vandergrift said. “In the day that those data are handed out it does feel like ‘oh my work is less valued than men’s work’.”

Availability of data

Vandergrift said that information has been distributed three times since she joined Faculty Senate. Several faculty expressed frustration that this information is not widely available or being discussed.

“I was aware that these are national trends,” marketing professor Radostina Purvanova said. “I was never aware this was true at Drake. That information should be more publicly available so that female professors can have more of a voice.”

Sociology professor Michael Haedicke echoed Purvanova’s statement.

“I do not think there is much broad discussion about gender inequality in pay,” Haedicke said. “There is the beginning of the discussion, but not a full conversation. One thing that would need to happen would be for the information to be widely available.”

President of Student Activists for Gender Equality Samantha Brenner was also unaware of the pay discrepancy.

“I actually have not heard much about it and we have not really talked that much about it at SAGE,” Brenner said. “Our last discussion of the year is women in economics so we will, I assume, talk a lot about that. However, I would not necessarily think to include Drake.”

Since Drake is a private institution, the university is not required to release faculty salary information.

However, many feel that data directly from the university would help find the cause behind the pay gap.

“Every year those numbers demonstrate inequality in pay,” Vandergrift said. “The interesting question is why that is. We have not had anyone bring answers to those questions to Faculty Senate.”

Director of Institutional Research Kevin Saunders said that Drake is more focused on aggregate date. Though his office does not deal directly with faculty salary information, he did say that the AAUP findings merit further analysis.

“The short answers is that people are not blind to your questions,” Saunders said. “It is a sensitive topic and a lot of factors that contribute. My perception is that when you look at those graphs it raises a question. Anytime that the question is raised it is important to take that next step.”

The next step for many faculty is finding what causes the pay disparity.

Field difference

One cause of the pay gap could be the large number of men in higher paying fields of study. The majority of full time faculty, 45 percent, are male. They also represent the majority in the highest paying fields like law and business.

“When you are going off of an average a single high or low number can influence the average,” Saunders said. “Let’s imagine that there is a handful of really high paid faculty members who are also male. They are going to tend to pull that up.“

The three highest paid faculty members for the 2010-2011 school year were all male, according to the 2011 tax-exempt form filed by the university.

However, women are the majority in the college of pharmacy and health sciences.

While Vandergrift agrees that field disparity may cause the pay gap, she is not ready to accept it as the sole reason.

“While some factors may appear to be individual, due to individual choices, like what field you go into or taking parental leave,” Vandergrift said. “The social organization of everyday life impacts the way people make choices.”

Service work and tenure

She believes that other factors like the distribution of service work also plays a role.

“You look at who gets the services awards, women are much more represented there,” Vandergrift said. “When you look at the tenure and promotion criteria, scholarship is something that is a clear and extremely important.”

Due to time constraints, English Professor Jennifer Perrine believes it is harder for a professor to excel in areas more highly valued by the university when they are involved in service work.

“Generally you have to be regarded as excellent in all of those areas: teaching, scholarship and service,” Perrine said. “For women, female faculty are given or take on cumbersome service obligations and committee appointments whose effects are often not as tangible as teaching evaluations or having research published.”

The reasons why women are involved in more service work vary. Vandergrift believes that women are viewed as more naturally “nurturing”. Perrine believes it has to due with rank.

“Those people (full professors) in general are not going to be delighted to do cumbersome service work when they can pass it to untenured faculty,” Perrine said. “(Women) can also propagate it once we get tenure.”

Of the 170 tenured professors at Drake, 101 are male. However, Haedicke believes that the trend is well documented nationally.

“Within my department the service obligations are distributed,” Haedicke said. “There are far more female and our department is chaired by a female. Service obligations are not just handed down. It is a question of if male faculty members find it easier to say no.”

Compounding effect

A survey conducted by LinkedIn showed that while 40 percent of men felt comfortable negotiating starting salary, only 26 percent of women felt comfortable. Several female professors said that they did not negotiate their salary when hired at Drake.

“When women are offered a salary they may feel less comfortable negotiating for a higher salary,” Perrine said. “Due to socialization, a lot of women do not have the option or think it casts an unfavorable light. Women would prefer to be liked rather than ask for what they want or need.”

Haedicke said that he did feel comfortable negotiating his starting salary but that there was not much room for discussion.

“I did, but Drake does not provide a lot of opportunity for negotiation,” Hadicke said. “There are really few things that people can negotiate.”

Purvanova said that she also felt comfortable but was unsuccessful in her attempt.

“I was not afraid that negotiating my starting salary was going to hurt me in any kind of way,” Purvanova said. “Maybe I was more willing to at least try the process because I know of the research that shows that women sell themselves short and are not willing to negotiate. I did not want to fall into that pattern. At least I tried.”

National trends

Drake does fall into a pattern. The AAUP survey showed the University of Iowa, Iowa State University and the University of Northern Iowa all had wage disparity between different gendered faculty members.

However, these trends do not satisfy all Drake professors.

“I am quite disappointed that these national trends are true at Drake,” Purvanova said.” That is not what the university claims to stand for. We supposedly stand for equality, for inclusivity. The pay disparity really does not live up to those high standards.”

Need for change

While money is not a consistently great motivator, Purovanova said, it can be a very effective demotivator.

“Drake is lucky that this type of information is not publicly available,” Purvanova said. “I would say that 99.9 percent of faculty are completely unaware of this information. If you are not aware you cannot be motivated or demotivated by it.”

Yet, money is not the ultimate goal.

“My point is that it is not about the number of dollars that you take home, Purvanova said. “It is that you are treated as a second-class citizen.”

“I would feel more valued as a faculty if I knew that Drake felt like as an institution it needed to be vigilant about this issue,” Vandergrift said.

Perrine said that any change would need to start with an inspection of the numbers.

“At a more institutional level, some more efforts being made to look at the numbers,” Perrine said. “For administrators who are approving salaries and raises looking at what they are offering.”

Brenner recommends that students voice their opinions.

“We have students here, who are paying tuition to go here and who therefore kind of have a say in what happens here,” Brenner said. “If people want to start a grassroots effort to change this it can happen. Other campuses have proved things like this work.”

A place to hear opinions on the subject is what Haedicke recommends.

“Conversations require collective energy, a place for people to have conversations, people who are invested,” Haedicke said. “That energy is invested elsewhere.”

Dina Smith • Feb 22, 2015 at 5:49 pm

The FSAR Review, Faculty Salary Administrative Review, only includes two women faculty outside of administration. Of the two non-administrative positions accorded to women, one is an Endowed Chair, and the other a Full Professor in Law.

Dina Smith • Feb 20, 2015 at 11:13 pm

The end of a conversation (on my side) with a senior administrator during Summer 2011, after I had inquired about the lack of a committee to evaluate faculty salaries. I researched and discovered faculty salary compensation was gendered (not to mention issues with college inequities). My concerns were dismissed.

I did all of this research out of necessity. With no savings, I had to go into debt to pay for a surgery to save my dog, Henry. Totally mercenary, at first, I wanted more money/year. But, then I became concerned after looking at the data, which was so incredibly gendered. Here’s the summer 2011 response to an administrator after a protracted conversation about the data. Clearly, I knew I wouldn’t be getting a raise anytime soon, then and now, and, hence, the reply:

“Good to know there is still a Salary Committee; bad to discover that it hasn’t met in a year (or longer).

And, I believe I read the table right: at Drake, Associate Professor women earn 70.7 (in thousands) in relation to men’s earnings at 77.4 — so $70,700 to $77,400 ($6,700 difference). And, yes, at the full Professor level, the gap is more profound: men earn on average $110,100 to women who earn $95,100 (a startling $15,000 difference). . .

That said, a gender schism occurs across our peer institutions, but this schism is most pronounced at Drake, I fear. Creighton has a worst record at the Professor level (men: 108.1, women: 84.6), but has less of a differential at the Associate level (men: 77.5, women: 75.2) . Bradley has a similar spread at the Associate Professor level (men: 73.6, women: 64.6) but is closer at the Professor level (men: 97.2, women: 91.5). Of course, I have read studies about faculty salaries becoming more gendered at the Associate and Professor levels because of attrition (women drop out of the academy/don’t get tenure, presumably because of children, and, thus, there are more male faculty at the Associate and full Professor level affecting the statistics). Of course, those same studies complicate the “attrition theory,” arguing that the academy suffers from the same bias as the corporate workplace, whose logic goes like this: “women, assumed to be the primary caregivers, work less because they have children, and, thus, they deserve less pay or worse.”

As for the argument that the market should determine faculty salary and thus Business and Law Professors unproblematically must earn more than A&S, Education. . . faculty, well, I will quote a mentor: “There should be an [A&S] Tax applied to all professional programs. We teach their students, help them become engaged, critical thinkers, writers, and decent human beings. Thus, we should not be seen as separate from those schools, nor should we be relegated to the university’s salary ghetto.”

There you have it.

Will Wright • Feb 20, 2015 at 3:24 pm

You speak to a couple potentially valid causes. Did you explore duration of employment as another potential factor?

Regardless of sex, I’d expect a tenured professor with more years experience as a tenured professor to make more money than a peer in the same department with fewer years experience.

The agenda of this article is quite clear. The argument for the “Field Difference” is weakly argued and contains confusing and unrelated statements. Conversely, the other notions are more strongly supported.

Criticisms of this piece aside, the premise should be explored further and with more statistical diligence.

Two of the best professors I ever had were women. I hope they’ve been getting paid more than their male counterparts. They deserve it.

David Courard-Hauri • Feb 18, 2015 at 1:31 pm

This is a really good topic to be bringing up; thanks for writing about it! I just wanted to point out a couple numerical things that you may want to correct. You write that female assistant professors make 4% less than male, amounting to a $400 difference. That would imply that male assistant professors make, on average, $10,000, which is significantly less than they actually make. Similarly, $2500 is 11% of about $23,000, which is too low for associate professors. Your $13,500 number suggests that full professors make an average of about $112,000, which might be right if it includes Law and Business, but seems high to me. I guess I’m just saying that you might want to check your percentages. Also, you say “The majority of full time faculty, 45 percent, are male.” Not sure what you mean to say here.