Over the summer, the Supreme Court ruled against the admissions programs of Harvard University and the University of North Carolina, ending affirmative action in the college admissions process. Before the decision, race already wasn’t a factor in Drake University admissions, according to Provost Sue Mattison.

“Affirmative action, with regards to admissions, only impacts those really highly selective institutions that limit the number of incoming students,” Mattison said. “So that doesn’t apply to Drake and most institutions across the country.”

She said schools like Harvard and UNC have enough applicants that they can pick and choose which applicants fill a certain number of spots.

Drake’s admissions team found that the university has “admitted all students who have a 3.0 high school GPA or [higher],” Mattison said. “Even though we’ve asked for a person’s race on the admissions form, it does not have an impact on the admissions decision, and it doesn’t displace anybody.”

Possible effects of the court’s ruling

Mark Kende, director of Drake’s Constitutional Law Center, said the Supreme Court “basically has embraced an idea that it calls colorblindness.”

“If you take their principle of colorblindness and extend it beyond universities, to other places, it could raise some problems,” Kende said. “But we don’t know yet.”

University financial aid programs that prioritize applicants of a particular race over another are more vulnerable after the court’s decision, according to Kende. He said it’s not clear what impact the decision might have on university hiring practices that consider an employee’s race, as well as corporations’ diversity programs.

Following the Supreme Court’s decision, Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey said Missouri institutions subject to the U.S. Constitution or Title VI must stop using race-based standards “to make decisions about things like admissions, scholarships, programs and employment.”

The University of Missouri System said that “a small number of our programs and scholarships have used race/ethnicity as a factor for admissions and scholarships,” and that “these practices will be discontinued.”

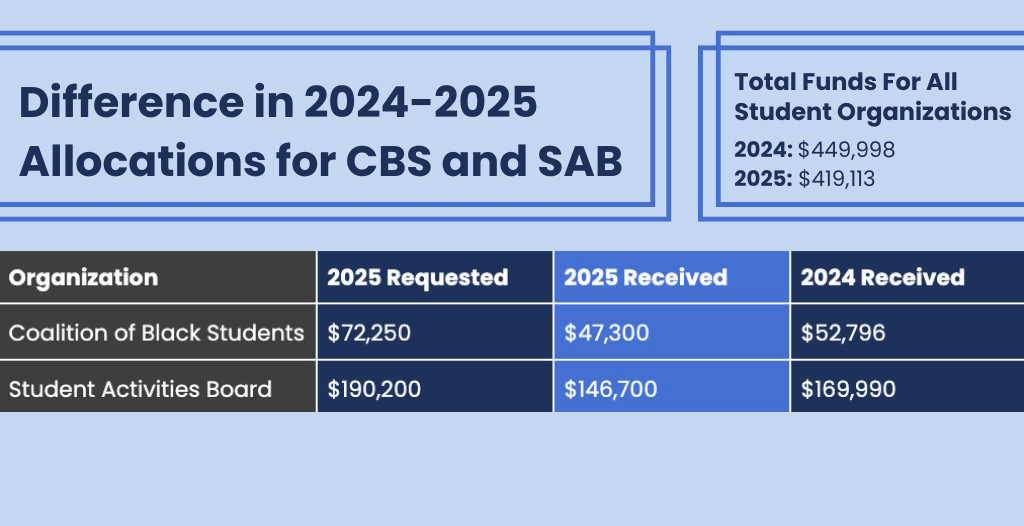

Drake is taking a different approach in the wake of the affirmative action decision. The university is monitoring maybe about forty to fifty scholarships, according to Ryan Zantingh, Drake’s director of financial aid. This is more in anticipation of a comparable case on financial aid that considers race, rather than a reaction to the affirmative action ruling.

Mattison said there are ways Drake can ensure the university continues its Crew Scholars program while still complying with the law. The program is for incoming students of color, according to Jazlin Coley-Smith, Drake’s director of equity and inclusion.

Coley-Smith said over email that “our intention is to meet the minimum requirements outlined in the ruling and to support our students.” Even with the affirmative action decision on the books, Zantingh expects Drake will continue providing financial aid to Crew Scholars.

“In light of the recent ruling, Crew Scholar leadership is actively working with campus leaders under the guidance of the university’s legal counsel to evaluate and fully comprehend the implications it may have on the Crew Scholars Program,” Coley-Smith said.

Donors for some Drake scholarships specified that they wanted to support a student of color or a woman in a STEM field, Mattison said.

“And so we’re still working through what that actually means, and what we have to do to continue to achieve the values that we expect,” Mattison said. “There are ways that we can change the wording of some of the scholarships.”

Like all students, students of color may qualify for scholarships for first-generation students or students with financial need.

“There’s a lot of overlap between students of color and other areas where financial aid is directed,” Zantingh said. “Scholarship resources can be directed [to financial need or first generation status] and still reach the same students.”

Editor’s note: After the article was published, Zantingh sought to elaborate on the above quote in this way:

“Only a fraction of a percent of Drake’s financial aid considers a student’s race. The vast majority of the aid offered to students of color is awarded on the basis of merit, financial need, or other factors such as first-generation status. There are multiple avenues to support students from underserved communities, and Drake commitment to doing so remains unchanged,” Zantingh said via email.

Even if there is a ruling on financial aid that’s comparable to the affirmative action decision, Zantingh doesn’t expect a large impact on Drake financial aid from either decision.

“There may be some implications, but I think the overall general effect on students will be little to none,” Zantingh said.

Zantingh gave an example of scholarship language offered by legal counsel. If a scholarship is for only minority students, it might become a scholarship that gives preference to students who demonstrate a commitment to Drake’s vision for diversity on campus.

“If a white student is actively involved in anti-racist leadership here on campus, certainly they would fit that description then, wouldn’t they?” Zantingh said. “Basically, the language would not seek to exclude any particular protected class categorically.”

In some cases, a donor might be unwilling to change the scholarship’s language or be deceased, Zantingh said. If a donor is deceased, a judge might approve changes. He said he doesn’t expect Drake to cut any of the scholarships it is monitoring.

“The scholarship criteria would have to change, or the dollars would have to be repurposed in another way. Per either the donor or a court’s approval,” Zantingh said.

Race can still play a role in college admissions

The Supreme Court left at least one legal path open for race to play a role in college admissions.

When admitting students, universities are allowed to consider “an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration or otherwise,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the Court’s decision. However, “the student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual — not on the basis of race.”

A student’s story can emerge without Drake asking for it, according to Dean of Admissions Joel Johnson.

“Especially if they’ve overcome a lot, or it’s so key to their identity… it’ll come out on its own,” Johnson said. “I don’t know if I could say the Supreme Court protected it. They couldn’t have stopped it, honestly.”

Johnson said that caring about diversity also means intentionally recruiting a diverse group of students. He said students can’t join Drake if they never apply in the first place.

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision on affirmative action, The Times-Delphic is publishing a series. Check next week’s paper for an article about legacy admissions and legacy financial aid with a Drake focus.