Drake University’s budget has come under scrutiny since the University cut registered student organization budgets and proposed the elimination of programs. To understand Drake’s budget challenges, The Times-Delphic investigated national trends in college enrollment and interviewed top university officials.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted higher education across the globe, making it difficult for universities like Drake to “draw any conclusions” about future enrollment, President Marty Martin said in an interview with the TD last November.

Universities rely on enrollment predictions to inform their budgeting decisions. According to a Chronicle for Higher Education article published this February, many colleges have long-relied on 18-year-olds who enroll full-time for eight semesters, so even a minimal decline in enrollment is significant.

This is especially true when universities see a significant decline in expected incoming first-year enrollment.

“A 50 student fluctuation in enrollment is a multimillion dollar hit to the budget,” Matthew Zwier, the former president of Drake’s Faculty Senate, said during an interview in 2022.*

Drake not immune to national decline in college enrollment

Colleges across the nation have seen a decline in undergraduate enrollment and are coping with financial fallback from the pandemic. Undergraduate enrollment in the U.S. decreased 7.8% between fall of 2019 and fall of 2021, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

“What we saw is that this college-going rate has not rebounded [from the pandemic] and the forecasts are that it won’t for some period of time, so that’s the new reality that we are planning against now,” Martin said.

According to the Chronicle article, colleges once expected student enrollment to peak in 2025, when the U.S. Census Bureau projected that the population of high school graduates would hit 3.5 million. After 2025, the Bureau predicted that this group would shrink by up to 15% over the next five to 10 years — a trend labeled the “enrollment cliff.”

Colleges were instead met by a divided reality: High school graduation rates are indeed up, but the share of those students who immediately go on to college is down by 6%.

“There were going to be more eligible students to go to college in these years than what was happening the years prior — and what’s certainly going to happen in 2026. But that’s all been erased by this decline in the college going percentage,” Martin said.

Chief Financial Officer Adam Voigts said Drake is aware of the predicted “enrollment cliff” and is taking steps to adjust the University’s operating budget to account for less revenue from tuition and fees.

Drake looks to balance budget in FY 2026

Each April, the Board of Trustees approves Drake’s budget for the following fiscal year, which starts on July 1. When Drake approves a deficit budget, it plans for its expenses to exceed its revenues. According to Voigts, the Board approved a deficit budget of $4.35 million for FY 2024.

In November, Drake predicted that the FY 2025 budget deficit would reach $10.3 million “if no action to curb the deficit were taken,” Voigts said in an email. After recent cost-saving measures, the University now expects a smaller deficit in FY 2025 than FY 2024, so this $10.3 million figure will decrease.

Voigts said the University expects to balance its budget in 2026. According to a Faculty Senate meeting on Jan. 31, Drake needs to cut $14.3 million from its $132 million operating budget, or just under 11%, based on a budgeting exercise in 2023.

“With the actions we have already taken to realize savings in FY24 and FY25, we are on track to achieve a balanced budget by FY26,” Voigts said.

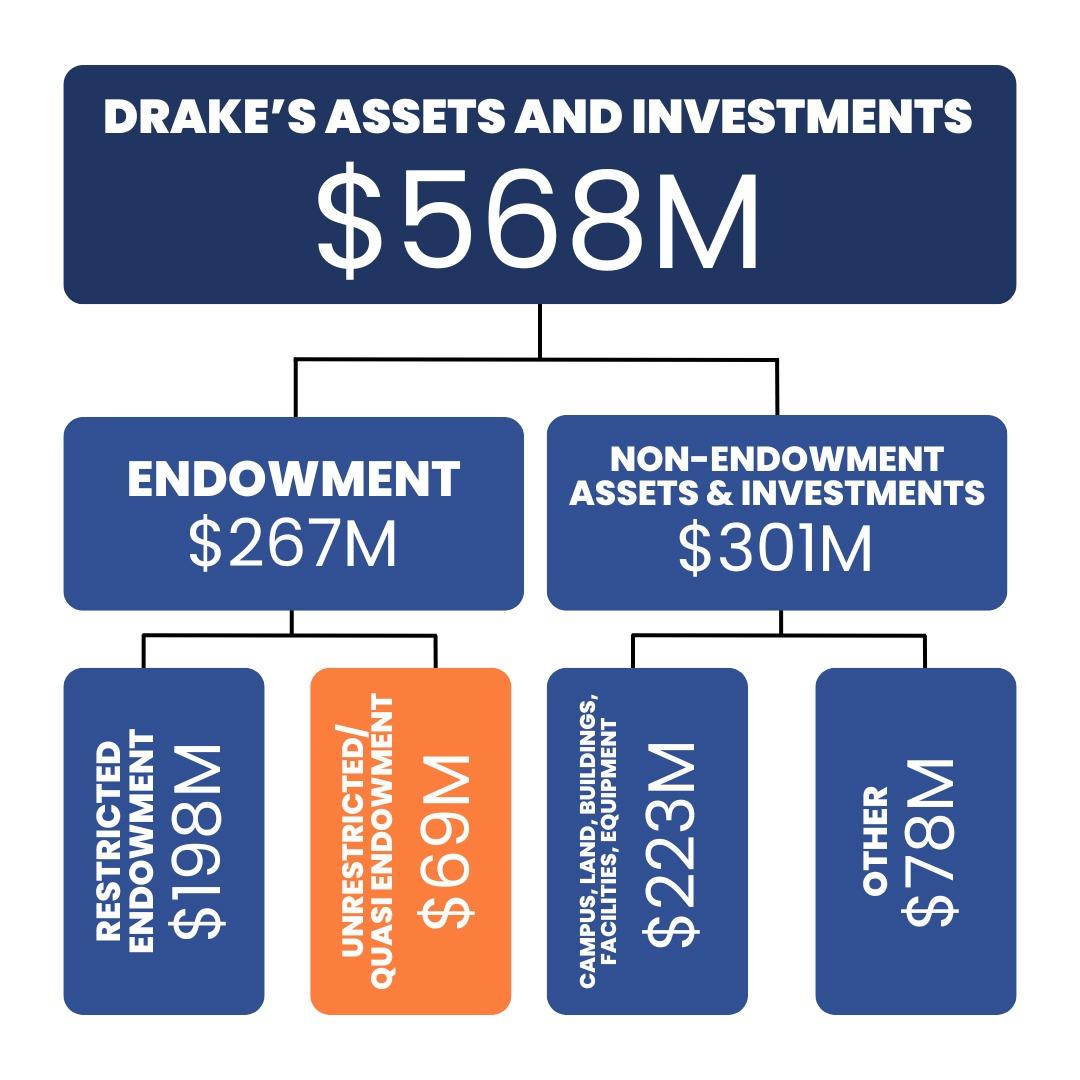

Most of Drake’s $267 million total endowment is restricted, meaning that donors have earmarked the money for a specific purpose — such as scholarships and endowed professor positions. When a fiscal year ends in a deficit, as it will this June and next June, Drake draws funds from the unrestricted portion of the endowment, which was most recently valued at $69 million. If Drake didn’t balance its budget, multiple deficit years would drain the unrestricted endowment.

“Continuing to run deficits will eventually exhaust the reserves and severely hamper Drake’s long-term financial stability,” Voigts said.

Universities invest much of their endowments in the market. An endowment’s investment return impacts a university’s long-term financial health, but fluctuations are “typical,” according to Voigts. Enrollment, by contrast, immediately impacts a university’s operating revenues.

“At Drake, and in higher education as a whole, enrollment has exerted a far more significant influence than market conditions in recent years,” Voigts said.

According to a 2022 publication from the National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA financial services, Drake’s endowment’s market value ranked 315 out of 685 U.S. and Canadian institutions.

COVID and unrealized enrollment predictions contributed to Drake’s budget issues

Like most institutions of higher education, Drake was forced to adjust its operating budget during the pandemic. Campus health precautions and hybrid learning incurred Drake “millions of dollars in additional expenses,” according to Martin.

“COVID was just a major event for the entire country but particularly hit institutions like Drake, where we live because we live face to face — residence halls, classrooms, dining halls, et cetera, and that had an impact on revenues,” Martin said.

Drake leaders involved in the budgeting process recognized that the financial consequences of the pandemic would be felt for years to come.

Martin said that, in March 2021, Drake thought it could balance its 2025 budget without continuing cost-saving measures implemented in 2020. Multiple faculty members had expressed anger at the cost-saving measures, which included temporary salary cuts and suspensions of contributions to faculty retirement plans.

That March, Drake was preparing to submit its FY 2022 budget to the Board of Trustees for approval.

“Our original plan was to maintain those [salary] reductions through the entire fiscal year,” Martin said. “…There was no way to be certain that we weren’t going to need [the reductions] anymore in order to maintain a balanced budget, but I felt like the evidence was strongly suggesting that we wouldn’t need it.”

Amid this evidence was the prediction that 2023, 2024 and 2025 would be “good years for colleges and universities in terms of enrollment.”

“2023, 2024, 2025 were supposed to be good because we have actually an increase in the total number of 18-year-olds graduating from high school and an increase in the graduation rate,” Martin said during an interview in October.

The University realized that the budget situation wasn’t going to improve while establishing the budget for FY 2024, Voigts said.

Administrators say Drake is financially healthy

According to Drake’s internal website “Shaping Our Future,” the University has low debt in comparison to its assets.

“Drake’s opportunity for financial improvement is in balancing our operating budget,” the website says, and Drake will do so “through innovation and revenue generation, but also by reducing our expenses.”

In support of Drake’s financial health, Voigts referenced Drake’s composite score, a measure of an institution’s relative financial health calculated by the Department of Education. On a scale from -1.0 to 3.0, Drake is rated 2.8 as of June 30, 2023, according to Voigts.

The Institute of Educational Sciences (IPEDS) publishes yearly reports on institutions of higher education in the U.S. detailing institutions’ admissions, enrollment, financial aid, graduation rate, expenses and revenues and staff pay statistics. These reports compare Drake to a custom comparison group, which is chosen by Drake, that includes Bradley University, Butler University, Creighton University, DePaul University, Elon University, Gonzaga University, Loyola Marymount University, Loyola University Chicago, Marquette University, Santa Clara University, St. Thomas University, Texas Christian University, University of Tulsa, Valparaiso University and Villanova University.

A few trends in the reports include:

Drake’s enrollment has decreased by approximately 100 students per fiscal year, while enrollment at its comparison group has remained stable.

| Drake | Comparison Group | |

| 2020 | 5,626 | 9,423 |

| 2021 | 5,504 | 9,509 |

| 2022 | 5,416 | 9,402 |

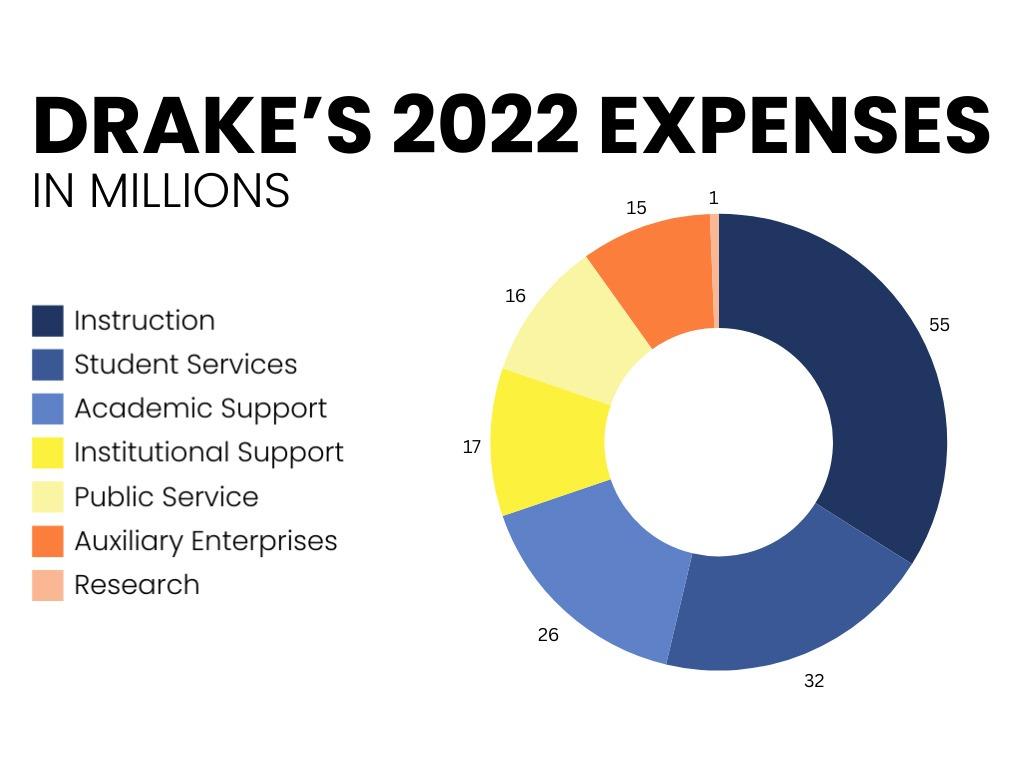

As a factor of full-time equivalent (FTE) enrollment, Drake spends less on instruction than the comparison group.

| Drake | Comparison Group | |

| 2020 | $12,797 | $15,274 |

| 2021 | $11,766 | $13,730 |

| 2022 | $12,592 | $14,703 |

Private gifts, grants and contracts consistently comprise a greater proposition of Drake’s revenue than its peer institutions.

| Drake | Comparison Group | |

| 2020 | 20% | 12% |

| 2021 | 17% | 11% |

| 2022 | 10% | 9% |

Most fundraised gifts do not prop up the operational budget

Voigts said that enrollment and endowment support are “two of the most significant factors that contribute to the University’s overall financial well-being.” Giving support, which consists of donors’ annual gifts as well as gifts to campaigns, are also significant contributors, he said.

Like many contributions to the endowment, however, most fundraised monies are restricted. In other words, these funds cannot be diverted to support general University operations.

“Fundraising and institutional fundraising campaigns historically don’t solve financial problems with an institution,” Vice President for University Advancement John Smith said during an interview in December. “…I always positioned philanthropy as the vehicle that enhances and transforms an institution, but tuition revenue and those traditional lines of revenue are the important operational funding that sustains an institution.”

Smith said the University positions its fundraising campaigns towards “aspiring ideas and inspirational ideas” — rhetoric that is attractive for donors.

“Successful fundraising at Drake University — and all organizations — is grounded in donors’ confidence in the strength and long-term viability of the institution,” Smith said in an email. “Historically, prospects do not respond well to short-term needs. Instead, prospects want to invest in organizations that produce — and can be — positive agents of change in the communities of which they are a part.”

Donors who wish to support the immediate needs of the institution can give to The Drake Fund. The University recently raised $775,680 for The Drake Fund, which is a component of “The Ones” Campaign, during its annual 24-hour All In Campaign. In total, the University has raised $216 million for “The Ones”.

How Drake goes about fundraising for its immediate operations versus its forward-thinking initiatives has raised questions about whether the University could go about fundraising differently.

“Faculty are struggling with the apparent disconnect between a really successful [‘The Ones’] campaign and the budget crisis that we find ourselves in,” professor Debra DeLaet said during the Dec. 13 Faculty Senate meeting. “…Could a portion — even a very small portion — of every donation be directed towards operational funds as a way of signaling that we need these things to be connected? And that doesn’t diminish the commitment that donors have to wanting to donate their money to things that they’re particularly passionate about.”

Even amid budget deficits and program review, the University has not seen a decrease in the number of people investing in Drake, Smith said.

“Organizations go through these cycles, but it’s how you manage through it and how you position both yourself as in the present and the future that [determines whether donors] have the confidence that ‘I’m still going to make that investment,’” Smith said.

Andrew Kennard contributed reporting.

*According to U.S. Department of Education data, Drake’s average annual cost of attendance is $29,098. According to a chart provided to The TD by Chief Student Affairs Officer Jerry Parker, incoming students will pay an average of $12,155 for room and board during the academic year 2024-2025. Combined and multiplied by 50, an unexpected loss of 50 incoming students could cost Drake $2,062,650 in a given year.