Faced with angry mobs and threatened with death, more than 400 college students known as the Freedom Riders started the wheels in motion for civil rights activism on college campuses in the 1960s.

But 50 years after the journey of the original Freedom Riders, many students still find themselves grappling with the meaning of equality in higher education.

“On a national scale I would say very little has changed,” said Lawrence Crawford, a Drake alum who worked in the admissions office and served as the president of the Coalition of Black Students. “I think that a lot of minority populations, blacks included, had to become a lot more aggressive in trying to defend the rights that they have. In some senses the younger populations are a lot less aggressive, a lot more complacent and a lot less reflective on battles and struggles that have foregone by our grandparents.”

According to Drake’s mission statement, the university strives to provide responsible global citizenship and meaningful personal lives for its students. But critics say that vision is undermined by the low enrollment and employment of minorities.

According to the university databook, Drake has 193 black undergraduate students out of roughly 3,500 and six black faculty members of 274.

“It’s become extremely difficult for me personally to sell this university because I feel like in some instances I’m selling a false promise of what I expect Drake to be,” Crawford said.

Unrest is not solely seated among students but also with faculty members who express concern regarding the lack of change occurring on campus.

“In my view it’s a crisis,” said Melissa Klimaszewski, assistant professor of English at Drake and the advisor of the Coalition of Black Students. “I think that it’s something that everyone on the campus should feel as a crisis, regardless of how you identify personally.”

Despite university goals of diversity and multiculturalism, the meager black representation on campus is a statistic that top administrators acknowledge.

“I don’t think that we are nearly as diverse as we need to be in any way whatsoever, either at the student or faculty and staff level,” Drake President David Maxwell said.

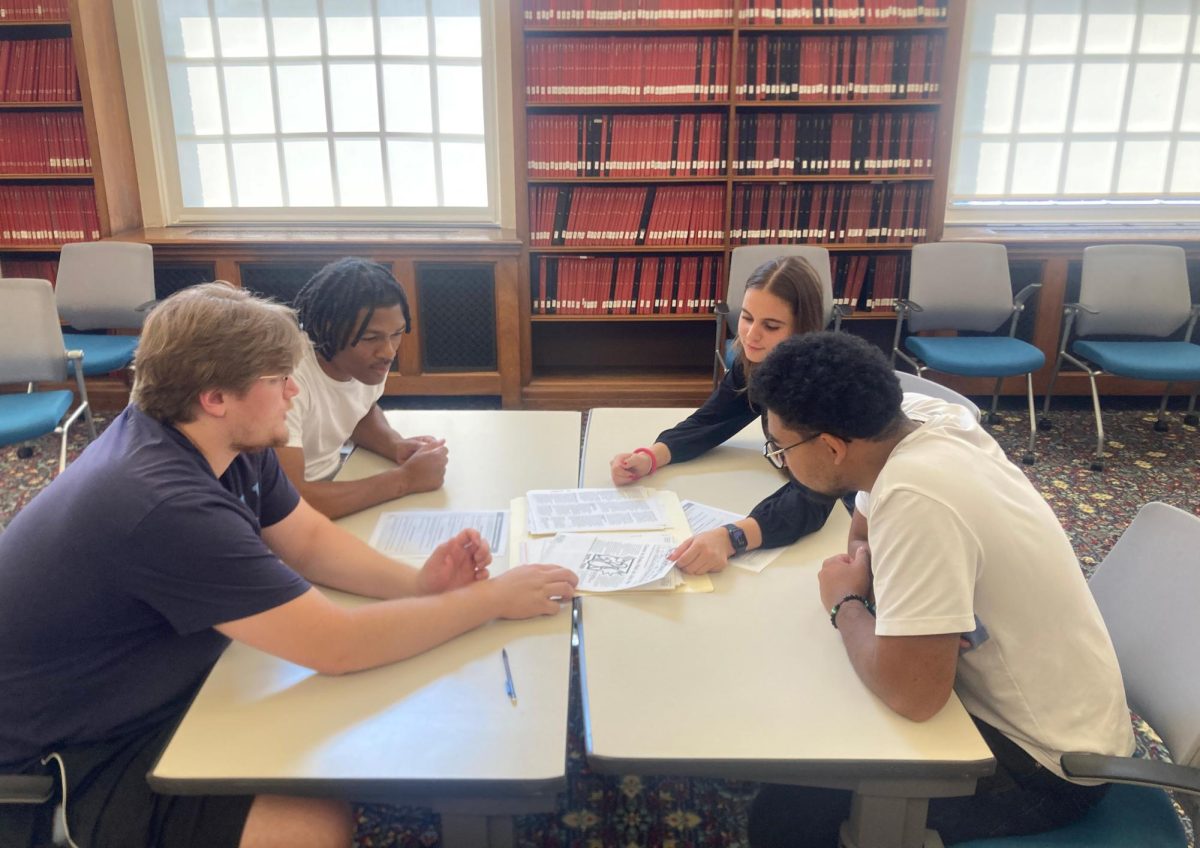

Challenges regarding diversity and global identity also affect the ways students interact on a daily basis at Drake, both socially and academically.

“I think if you want to argue that Drake is desegregated, you can go into Hubbell and look at the tables and you will see that Drake is not desegregated, socially at least,” junior Ryan Price said. “If you just look at where people sit in the dining hall, it’s pretty clear that we don’t integrate too well.”

Although many students note racial segregation, not just among black students, in social settings at Drake, they are also quick to note the respect that multicultural organizations receive on campus.

Also readily identified is the fact that the Drake community as a whole struggles with student unity and creating a cohesive social climate.

“Our student body is just not on one accord,” Crawford said. “That’s one thing that I loathe from Drake and really envy in other schools. They have this group sync within their student body population.”

A lack of integration between Greek, multicultural and athletic programs inhibits students from seeking relationships with others and hinders racial understanding, Price said.

“It’s not so much the fact of having diversity but what you do with that diversity that matters,” Price said. “I think it’s about understanding as a verb instead of diversity as a noun.”

A key aspect in building such understanding comes not only from acceptance of Drake’s student population but also the surrounding Des Moines area.

“People that say that paint a horrible picture not just of the neighborhood but of the people that live in these neighborhoods,” Crawford said. “And it’s like, ‘Ok, there goes another stereotype that just got perpetuated.’”

On Drake’s campus, where barely 0.05 percent of the undergraduate student population is black, the admissions office struggles not only to recruit a wide variety of students but also to provide diverse admissions counselors that students can relate to, Crawford said.

Maxwell says that the applicant pool of black high school graduates who meet Drake’s standards is increasingly small.

However, the university does not offer any form of minority scholarships to entice top minority students to choose Drake over other institutions.

“Our best shot at becoming more diverse has a big part in fulfilling our social compact with our community to improve the success and college readiness in Des Moines schools,” Maxwell said.

While Crawford recognizes that the university is striving to incite change both within the Des Moines community and within its own administration, the lack of student representation for African Americans is nonnegotiable.

“I love Drake,” Crawford said. “I think that we really try very hard on so many different platforms and so many different levels to reach this, but there are some things we are just dropping the ball on. And it’s not a good look for perspective students.”

Despite university involvement and community coalitions, the number of black students graduating high school with a high level of college readiness is on the decline, Maxwell said. Coupled with insufficient university funds to provide aid, the problem of creating equal representation at Drake will not easily be resolved.

“The most discouraging thing for me is that I was having this conversation 30 years ago when I was at Tufts University and we haven’t gotten any better,” Maxwell said.

student • Aug 22, 2011 at 4:17 pm

I understand the concerns, but I’m not sure if responsible global citizenship and meaningful personal lives is what I’d associate with this issue. Global citizenship and meaningful personal life goes beyond some statistics on population of different races on campus.