The students of Drake University exist in a concrete bubble defined by the intersection of Forest and University Ave. Within the halls of academia, the outside world slips away, replaced by essays, labs and late-night emails. The coronavirus has only made the connection to nature more tenuous.

Urban Environmental History students have chosen to venture out into the city, armed with environmental and historical knowledge to help them understand Des Moines and the privileges they have.

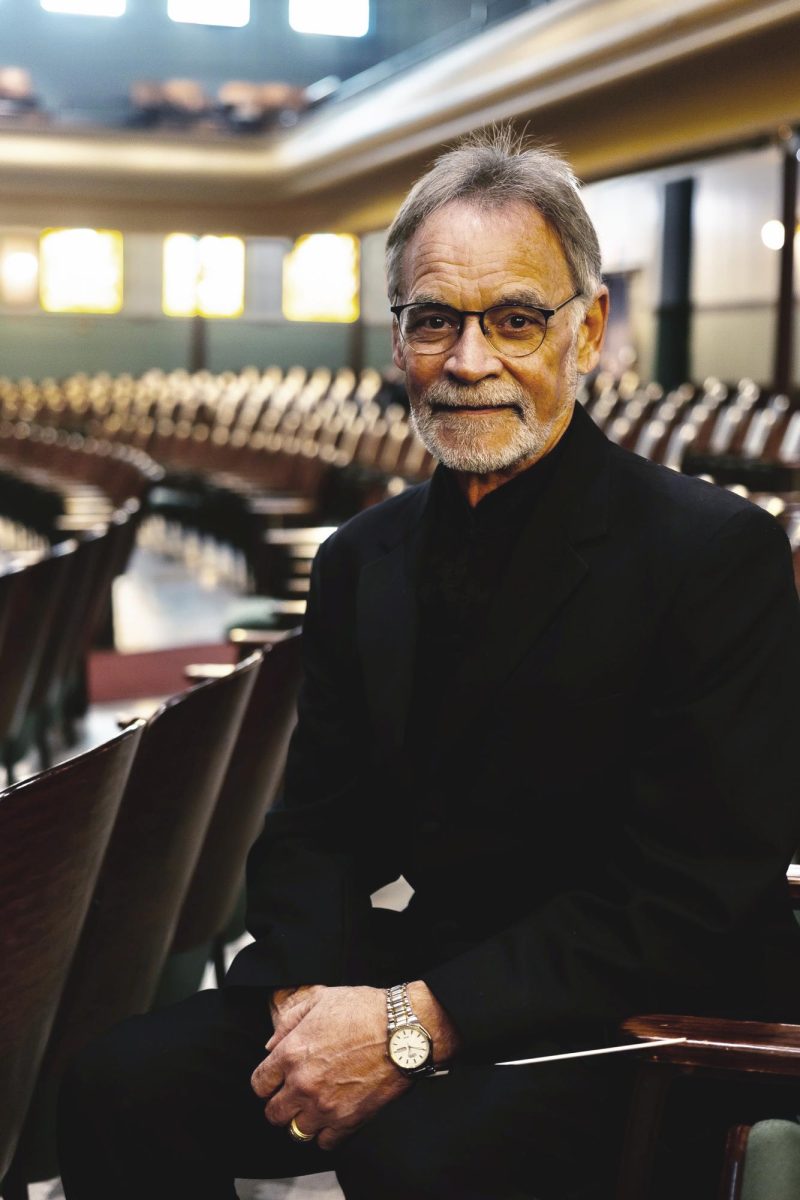

Urban Environmental History, or HIST 188, is a small class of twenty. The course material is broad rather than deep, and thus open and applicable to all majors. They meet twice a week to unite the ideas of cities and the environment, an important idea for college students living in Des Moines.

“Most people think of the environment, and they think of forests and mountains,” said Amahia Mallea, professor of the class and environmental historian. “As long as people think that the city is not nature or that it’s failed nature, then they will fail to see the way their actual relationship with the environment functions.”

The class aims to ratify this by sending students out into the city once a week.

“That week we were talking about infrastructure, so we noticed the flags on the ground, different manhole covers, powerlines and the community gardens,” Jacob Lish, HIST 118 student and environmental science major, said.

The class teaches through real-life experiences.

“As I’m walking around the neighborhood, I’m feeling more a part of it,” Lish said. “Most of my first year I stayed on campus and didn’t leave much. Exploring the neighborhood has made it less of a separate area.”

The layout of the city itself has created a disconnect with the rest of Des Moines. Mallea pointed out the “moat” of parking lots around Drake’s campus.

“You send a sign to a neighborhood when you tear down a bunch of houses to build a parking lot,” Mallea said.

She brought up Interstate 235 as well, a new highway that cuts through what used to be a residential area.

“For Drake students, I-235 disconnects them from downtown,” Mallea said. “Without the interstate system, students might feel a greater connection to downtown—we’re not actually very far away.”

A big theme in the class is accessibility in city design.

“We can see segregation and discrimination every day in the modes of transportation that people are using,” Mallea said.

While it is a privilege to be able to walk and ride a bike, the intersections near Drake are poorly designed for pedestrian use.

“This is a built environment that is giving the finger to pedestrians,” Mallea said. “It’s a free pass for people in cars to do whatever they want.”

Lish seconded this sentiment.

“The sidewalks aren’t always great,” Lish said. “There has to be a sidewalk legally, but that doesn’t mean it has to be in good repair or that there are easy places to cross the street.”

These create challenges for students looking to explore the city.

Urban Environment History teaches its students to find nature everywhere.

“It’s pretty beautiful how nature gets incorporated,” Abby White, class member and environmental science student, said. “I’ve gained a greater appreciation for the nature that we use, like [how] the wood that we’re sitting on was once a tree.”

Seeing nature around campus in small ways helps translate the big environmental issues the world faces.

“If we can’t understand the relationship that cities have to the world around them, how are we going to solve the climate change crisis?” Mallea said. “If we always come at it with the perspective that cities aren’t nature, or worse that cities are the antithesis of nature and that it’s a lost cause, there’s no hope to address climate change.”

Urban Environmental History will be offered at Drake in Fall 2021 for students hoping to localize modern environmental challenges.