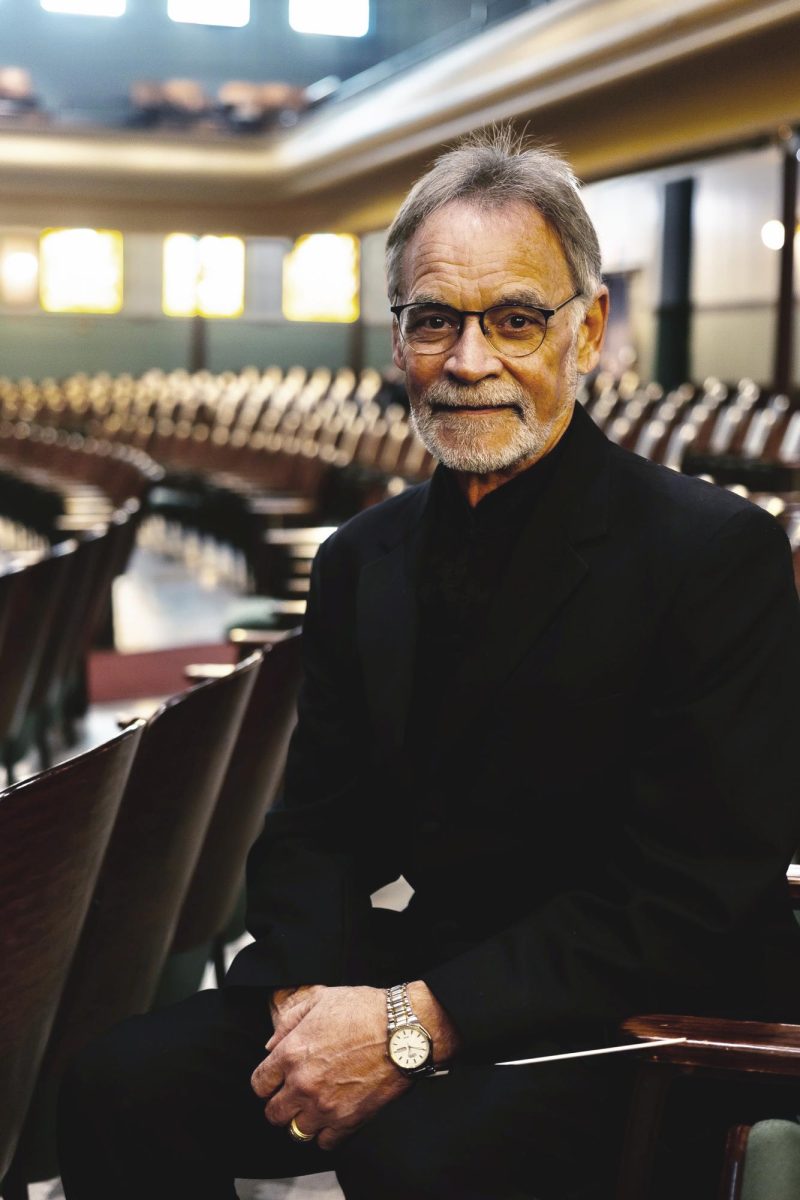

“There’s this misconception that young people love change,” said Chris Snider, an associate professor at Drake University’s School of Journalism and Mass Communication. “But young people don’t like change either. For the most part, people… fight against any sort of change.”

Snider’s role in the SJMC consists primarily of overseeing various social media accounts and teaching courses that focus on social media strategy. These positions allow Snider to closely monitor the shifting social media landscape through the lens of its college-aged user base, as well as the attitudes of those who engage with these platforms.

With legislation threatening to ban apps like TikTok in the U.S., it would appear that change is imminent. Despite this, however, Snider thinks there might not be as radical of a shift as people may be expecting.

“The social networks we use have not changed in a very long time,” Snider said, noting that since their introduction, the key players on the social media scene have consistently been Instagram, Snapchat and Youtube.

Although the big three remain the same, Snider pointed out that fragmentation has occurred. Apps like Threads and Bluesky have popped up as alternatives to X, formerly known as Twitter, and still more apps are popping onto the scene in anticipation of a void that will need filling should legislation banning TikTok in the U.S. pass once and for all.

Division in the digital sphere

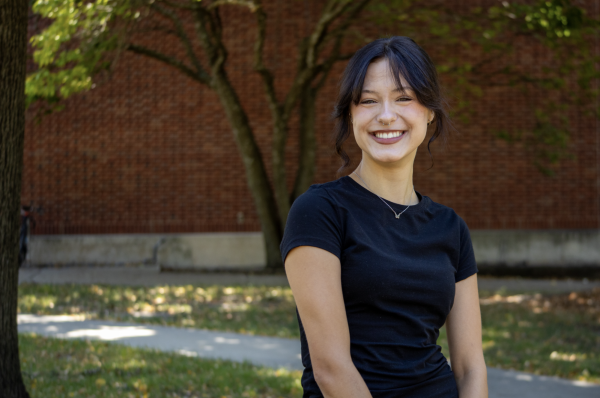

Katy Biddle, an assistant professor of communication at the University of Southern Mississippi, believes this fragmentation of the internet is contributing to more division in society as a whole.

“Students, and others as well, are constantly exposed to messages over social media in a way that they weren’t necessarily exposed before,” Biddle said.

The frequency with which we receive these messages is something Biddle says users need to be paying attention to, as with personalized feeds. It is easier now more than ever before to get lost in specialized messaging rabbit holes tailored to each individual user.

“[In the past when technologies have evolved], these higher-up people, these elites, would get concerned and think about how the little regular people might get indoctrinated because of the ideas that they hear,” Biddle said. “Research shows that that’s not necessarily true… but the thing is that now, these messages [are] able to be personalized to people, as opposed to one message that had to go out over broadcast and appeal to millions of people at once.”

In addition to her work as a professor, Biddle is also a researcher. She studies the relationship between people’s political beliefs and their social media usage, particularly examining how this relationship affects the way people conduct themselves online. Through this research, she has found that the strength of people’s parasocial relationships with the influencers or celebrities they follow has a tendency to ebb and flow with the political climate of the time, leading to even more decentralization of users’ online experiences.

“We have this tendency to think that everything we see online encapsulates someone’s entire personality, [but] that’s just not true,” Biddle said. “Even the people who are live streaming every single day, we’re still not going to see their entire life or all of their thoughts.”

Due to this near-constant inundation of digital messaging users consume, Biddle stressed that when creating content for social media, it is important to think about how those messages are constructed.

“The ethical side of not just consuming information, but making messages on social media should be focused on more,” Biddle said. “Having the critical analysis and critical thinking behind you before you say things can be really important.”

An artificial future

Another key movement to pay attention to on social media is the use of artificial intelligence, Snider said. With the growing expectation of humans to share every aspect of their personhood online to bots that purport to do just that, he cautioned users to stay vigilant online.

“Social media companies all want to be AI companies,” Snider said. “So we’re going to see AI in many ways in our social media. We’re going to be interacting more with AI content in our social feed.”

Although Snider predicts the volume of AI content users see online will increase, he made it clear that AI is already present in their feeds.

“A large percentage of what you see on LinkedIn is being written by AI. We just don’t realize it,” Snider said. “I think this future world where we work with AI… is what we’re heading toward, and it’s going to come to social media, and it’s going to come there faster than people realize.”

But if Snider is right in his observations and young people truly dislike change as much as everyone else, the likelihood of these changes to the digital landscape sticking around depends almost entirely on Gen Alpha, the generation after Gen Z.

“The people who don’t fight against change are the people who are brand new to it,” Snider said. “They say the real trends come from middle school girls because they’ve got time on their hands. They’re not afraid of being social… and they haven’t been doing something the same way for five or 10 years, so it doesn’t feel like change for them, it’s just something to do.”

Change is inevitable. Whether or not social media users decide to embrace it is a decision each person must make for themselves, Snider said. Love it or hate it, Biddle says users will have to tread carefully and remain conscious of the digital landscape around them.

“I don’t think social media is going away,” Biddle said. “But the ethical side of social media is really important [and] we… have an obligation to learn how to use it in a beneficial way for society.”