This fall, Hoover High School became the first high school in Des Moines to introduce a unique cell phone ban in its classrooms, a policy several educators hope will become commonplace for all American high schools in the next couple of years.

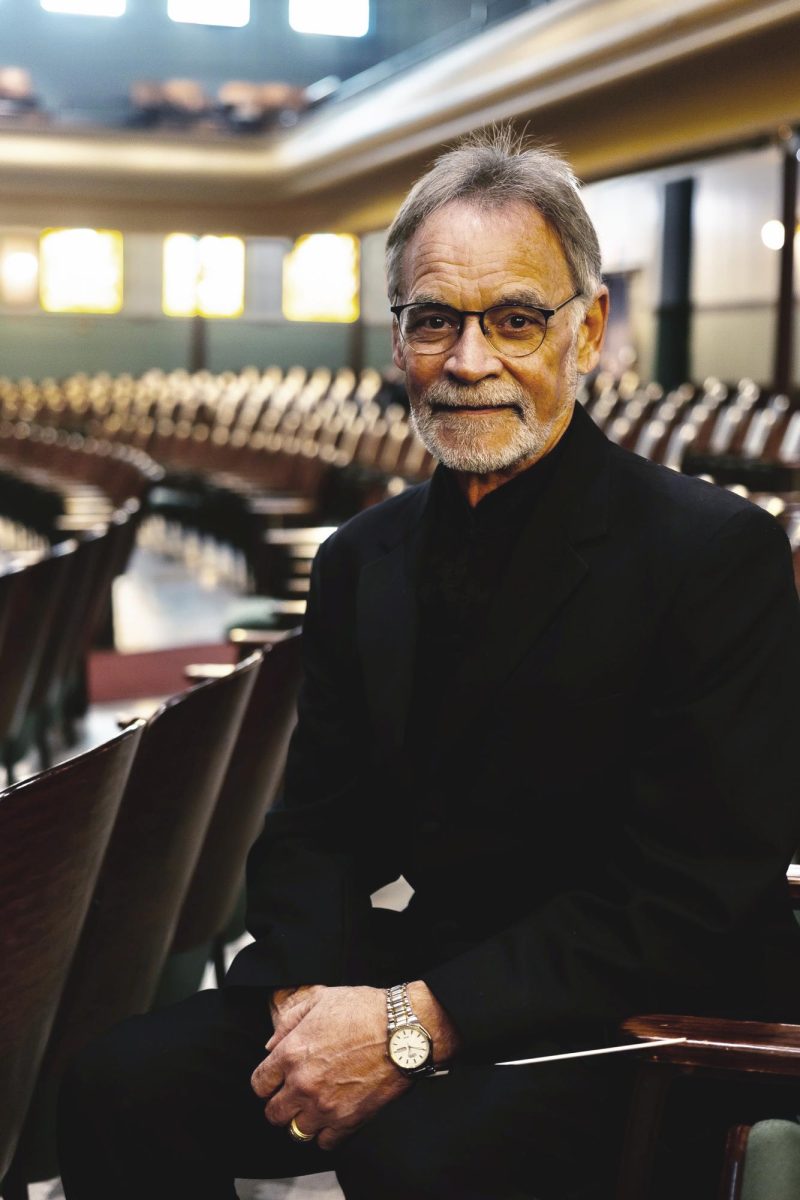

The ban is part of Hoover’s new “Mental Health Movement” — a three-part plan to help students recover from the negative effects of constant phone and social media use, educate parents on those effects and reconnect students to the Hoover community. Now, nearly three months into the school year, Hoover’s assistant principal Rob Randazzo said the effects have been “extremely positive.”

“The feedback we’re getting from students and from teachers has been tremendous,” Randazzo said. “I had a teacher say to me, ‘If you want to know what it’s like to teach in Heaven, come teach here at Hoover.’”

Randazzo said most students initially felt wary of the policy but have since come forward to express their gratitude for it. The phrase “I don’t like it, but I know I need it” is some of the most common feedback the administration hears.

One Hoover student sent Randazzo an unsolicited email about the ban and allowed the administration to share it.

“I feel like I’ve learned more in the past couple weeks at school than I learned [in] months with my phone,” the email said. “I actually think that I’m starting to enjoy school, and there’s no more stress of using my phone every second and seeing what my friends are doing.”

Richard Lock, a 2024 Drake graduate and music teacher at Southeast Polk Middle School, said his students feel a similar gratitude. Many middle schools already have policies that phones must stay out of sight during the school day, but Lock hopes it will become commonplace for all high schools to enforce these policies, too.

“Without phones in the classroom, students are able to focus on themselves and live in the moment more,” Lock said.

Both Randazzo and Lock reported that enforcing this policy brings its fair share of challenges. Randazzo said his teachers have seen a spike in certain behaviors in the classroom that never used to happen when phones acted as a “pacifier.”

Randazzo said he spoke to one student about why he continues to act out during class and the student responded, “I’m bored.” Lock noticed a similar pattern and gave a warning to his peers studying education at Drake, saying this generation of students struggles to stay engaged for long periods of time.

“Expect students to have attention spans the size of an acorn,” Lock said. “Students have chosen to rely on phones and tech to learn for them, and it allows them to be lazy and not read or look at assignments… instead of learning themselves.”

Additionally, though Randazzo said most parents have reported positive opinions of the new phone policy, both educators have heard from parents who fear not having a line of communication with their children in the case of a school shooting.

“This year at [Southeast Polk], there was a threat of someone bringing a gun to school,” Lock said. “Luckily, it was false, but if it was real and we needed to get out fast and didn’t have time to grab phones, as a parent, I would be terrified.”

During the planning stages of Hoover’s phone policy in early 2024, Randazzo said the Hoover administration had around 150 conversations with parents. He said that parents’ fear of a school shooting played an important role in the policy’s logistics. Students can have their phones with them during school, but they need to be put away in a backpack or purse. Only if a student is caught using it during class will a teacher call an administrator to come confiscate the phone for the rest of the day.

Randazzo feels confident that Hoover landed on a policy all parties are comfortable with and that they are making tremendous progress with getting all students on board. Of Hoover’s 925 students, he said that about 5% are still struggling to follow the rules, but he believes the consistency of teachers and staff will be key to overcoming these struggles.

Randazzo feels it would be hard for anyone to see the research around anxiety, depression and self-harm in kids today and oppose the cell phone ban.

“For me, it was no brainer that we have to play our part in schools,” Randazzo said. “We are in a mental health crisis in schools, and we… have to step up and do something.”

Because of this, Randazzo predicted that all schools in America would be phone-free in the next couple of years. In Iowa, several cities, including Davenport, Ottumwa and Ankeny, have already banned phones or are working toward a phone-ban policy in their high schools.

“I can’t say, ‘You know what? Let’s give it five more years and see what happens,’” Randazzo said. “I think it’s obvious what we need to do here in schools, because then what we’re doing in schools broadens the conversation that we all need to be doing around mental health right now.”