Rare Disease Day is an annual awareness event held on the final day of Feb. 28, or Feb. 29 during a Leap Year, is a day to draw attention to rare diseases as a public health issue.

Rare diseases, as the name suggests, affect a relatively small portion of the population. The National Human Genome Research Institute defines a rare disease as affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the United States.

Globally, there are several methods of identification of what counts as a rare disease. The European Union classifies a condition as rare if it affects fewer than one in every 2,000 individuals in the general population. Rare diseases are typically chronic, progressive and life-threatening.

There are more than 7,000 rare diseases, and together, they affect over 300 million people globally — or approximately 3.5% to 5.9% of the world’s population. 25-30 million Americans — or one in 10 — live with rare diseases.

The European Rare Disease Organisation first celebrated Rare Disease Day in Europe in 2008. In 2009, the National Organization for Rare Disorders joined the effort to support Rare Disease Day in the U.S.

Drake University’s Disability Coalition organized a tabling event in the Olmsted Center breezeway to raise awareness and celebrate the resilience of the rare disease community.

“It’s the rarest day ever. That’s why it’s Rare Disease Day. So, we thought today would be a good day to draw attention to all those who are living with, struggling with or striving regardless of their rare disease” said Riley Wilson, the secretary and treasurer of DISCO. Members of DISCO handed out zebra-print ribbon badges as part of their tabling event.

“The zebra is the symbol and mascot for rare diseases. There’s the common medical adage: ‘When you hear hoof beats, think horses, not zebras’ because medical professionals are trained to look for the most common causes of symptoms and complaints and rule them out before they go to the rare stuff,” Wilson said.

Obtaining an accurate diagnosis for a rare disease is difficult — it might take years, which can be essential for delaying or reversing the course of a disease.

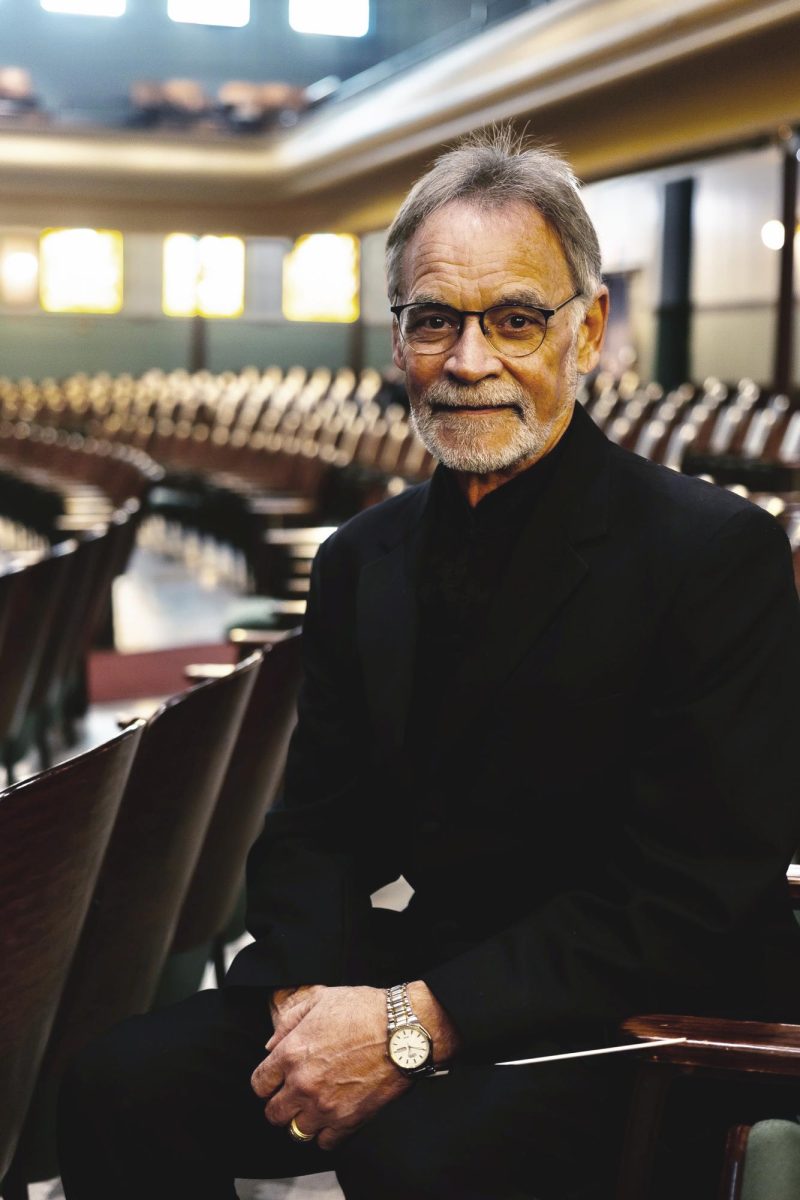

Lindsay Gilbert, an adjunct instructor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication, shared the story of her diagnosis. 10 years ago, she boarded a plane to San Antonio, Texas, and when she got off that plane, she felt like she was in constant motion.

“I kept joking that I was at the river walk in San Antonio, and that boats were going by us, and I kept saying, ‘Why do I feel like I’m riding on one of those boats, even though I’m walking on land?’” Gilbert said.

Her situation did not get better in the next few months.

“I ended up in an emergency situation where I was just so dizzy and struggling to maintain balance that I ended up getting an MRI and a variety of other things,” Gilbert said.

A neurologist finally diagnosed her with Mal de Débarquement syndrome, a rare disease marked by instability without dizziness — a feeling of continued motion after the termination of movement that can last for months or even years.

“[The neurologist] was able to determine that I didn’t have any of the other illnesses, and because mine was motion-triggered and I feel relief when I’m riding in cars, he was able to diagnose me [with MdDS] two years ago,” Gilbert said.

Due to the constant instability, motion sickness and nausea associated with the syndrome, Gilbert has developed migraines, chronic pain and another rare disease.

Medical professions are not actively researching many rare diseases and disorders. Patients are frequently treated “off-label” — given medications that the FDA have not approved for the specific ailment — which can result in insurance payment concerns for private insurance, Medicare and Medicaid. These therapies are typically more costly than those for common disorders.

“As someone who has more than one rare disease, it’s super important to raise awareness. All of my rare diseases don’t have treatments or any sort of medication to manage symptoms, and there are no cures. So, by raising awareness, we can work towards finding a treatment and raising money and awareness for clinical trials,” said Talia Prozument, programming chair of DISCO.

Patients diagnosed with rare diseases are often presented with limited or close to no treatment options due to a lack of research, medical knowledge and expertise. About 95% of the 7,000 known rare diseases have no treatment. 90% of all rare diseases have no FDA-approved medication, so informing the public and gaining their support is critical.

“Of all our rare diseases, only 5% of them have a cure, and mine is not one of them. So, what ends up happening is you end up going through a series of doctors who basically treat you like a lab rat and try and experiment and do different things to try to figure out what works best for you,” Gilbert said.

Gilbert found a combination of medications that help manage her symptoms to an extent, but they still persist in her everyday life.

Some rare diseases are “orphan diseases” — a category of severely neglected diseases whose therapies are frequently not regarded as cost-effective, owing to their high development costs and restricted patient population. The rarity of these diseases worsens the feeling of isolation, as finding support groups or people with similar shared experiences is incredibly difficult.

“If rare diseases impact 10% of our population, individually, each of us is really rare. For example, I’m one of two people in the state of Iowa with my illness, so it’s hard to find the support and the network without going online and having virtual support groups,” Gilbert said.

Gilbert participated in two breakout sessions on Health Professionals Day where she spoke about what it means to be a person living with a rare disease and how to treat individuals who live with rare diseases more like human beings and less like their diagnosis — seeing the human first, diagnosis second.

“Understanding that we’re not just one diagnosis, we’re not just one thing, is really important. So, I want to be seen as a human first. And yes, I live with rare diseases, but that’s not my only identity,” she said.

Because of a lack of public knowledge, people living with rare diseases and their struggles are frequently invisible and unrecognizable.

The Disability Coalition provides emotional support for people with disabilities and chronic illnesses on campus. They meet every other Sunday at 2 p.m. at the Harkin Institute to share personal experiences and discuss other issues on campus. They can be found on Instagram at the handle @disabilitycoalition.du.

Anand • Mar 6, 2024 at 10:12 pm

Very informative.