At the height of the Montgomery Bus Boycott in the 1950s, a man took a leave of absence from his job as a researcher at Time Magazine. He travelled all throughout the South with a microphone hidden in his briefcase, and he held the microphone up to shop owners and people on their front porches and people on the streets, looking to capture the American mentality at the onset of the civil rights movement.

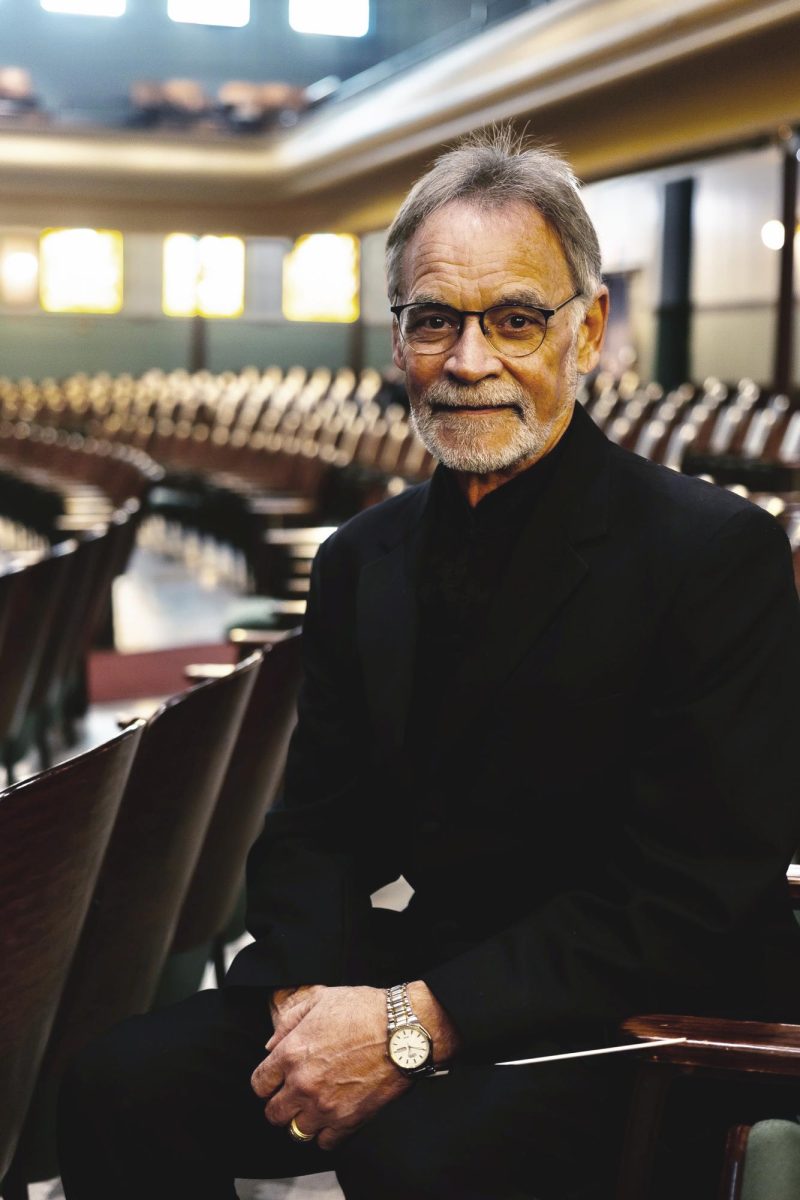

The man was Calvin Hicks, a 1956 Drake alumnus.

Hicks was one of the primary players in the black arts movement and has founded various activist groups, has written and edited for a plethora of activist publications in New York and has contributed philanthropy work to the transformation of African-American education at the collegiate level.

“It was a lot of responsibility and a lot of work, and we put up with a lot of danger,” Hicks said.

After the bus boycotts, he didn’t return to Time; instead, he joined the staff at a weekly newspaper in Harlem, N.Y., while he was simultaneously a member of the prestigious Harlem Writers Guild.

Leading up to the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the first legally elected Prime Minister of Congo after winning independence from Belgium, protests broke out worldwide. Many African-American activist groups in New York participated, many of them led by Hicks.

As a result of the protests, Hicks founded and chaired the On Guard Committee for Freedom. The group even published its own newspaper, and Hicks became the editor.

Shortly after, following the unjust kidnapping charge against Robert Williams in Monroe, N.C., Hicks became executive director of the Monroe Defense Committee.

Williams, who was head of the Monroe, N.C., chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, led a series of protests outside a local swimming pool that was off limits to black people. When a shooting broke out, Williams rushed two elderly white people into his home, and then he was subsequently charged with kidnapping. To escape arrest, he fled to Cuba and then to China, where he was openly welcomed.

“Robert (Williams) was something of a hero,” Hicks said.

All the while, Hicks wrote for Freedomways and New Challenge, and he was also a full-time reporter for New York Age newspaper. He also co-founded Umbra Magazine, one of the first post-civil rights black literary groups to establish a distinct voice among the prevailing white literary influence.

Hicks said the events of the times made putting together these publications unsafe at times but worth the risks.

“I also saw a lot of potential for real change in not only the laws but the revolution of people’s consciousness,” Hicks said. “Bearing witness to the possible expansion of people’s consciousness as well as my own was certainly inspiring, but it was not an easy thing to do over a long period of time, day after day. It could very easily take an emotional toll if one wasn’t careful.”

Hicks considers himself privileged to have been able to meet so many activists and civil rights leaders over the years. He’s met members of the Pan-Africanist Movement, people who played an important role in South Africa during apartheid, activists who were well known and those who were not.

“It was extraordinary,” Hicks said. “That’s something that’s irreplaceable. I think I was very fortunate to be alive at a certain age during that period.”

Hicks had his sights set on becoming an activist as a young teenager. His mother was involved in local politics in Boston, and the push for change is something Hicks has always been surrounded by.

“It was all around me. Our house was very often a gathering place for all sorts of issues on local neighborhood politics or international issues,” Hicks said. “It was the norm. There wasn’t any active prodding (to become an activist). It was the way it was.”

Through her involvement in local politics, Hicks’ mother, Marguerite, worked closely with the editor of the Boston Chronicle, William Harrison. While in high school, Hicks approached Harrison about any contributions he could make to the paper. Harrison kept him busy.

“There were a lot of stories I did on my own initiative,” Hicks said. “It was a great learning experience, especially at a fairly young age.”

When it came time to search for colleges, Hicks was positive he wanted to flee Boston — the entire New England region, in fact.

In 1951, Drake University made national headlines with an incident that prompted Hicks to venture to the Midwest.

A Drake African-American football player, Johnny Bright, took an intentional blow to the jaw from an Oklahoma A&M player, which knocked him unconscious and broke his jawbone. The incident provoked change in the NCAA safety mandates in helmet and face guards.

The “Johnny Bright Incident” caught Hicks’ attention, eventually leading him to learn more about Drake itself. And so, on a whim, Hicks chose the school and chose to study journalism.

Hicks wrote for The Times-Delphic and was especially fond of a few journalism professors.

“The person who was head of the journalism school at the time, he was very influential on me,” Hicks said. “He took some real interest in me. My involvement with the paper and the head of the journalism school had a very positive influence on me.”

After Drake, Hicks wrote briefly for the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper before moving to New York in 1957.

In 1969, Hicks was offered a professorship position in the sociology department at Brandeis University near Boston — the first African-American to be offered the position. He had also been an adjunct professor at Brooklyn College and at Long Island University before becoming director of the Third World Center at Brown University and a professor in the department of African-American studies there.

“By the time I began teaching, I was less politically motivated than I was intellectually motivated, or there was a greater fusion between politics and intellectuality,” said Hicks. “I think I viewed teaching as an extension of the work I had been doing organizationally. I had been taking my role into a different venue.”

But gradually, after teaching for a while, Hicks began to notice something, primarily after his work at Brandeis University.

“After Brandeis, I was becoming somewhat cynical about the way black students were being treated with a lot of paternalism,” he said. “They were not being held academically and intellectually accountable. (Universities) were not treating black students as human beings, but as a cast.”

At Brown University, Hicks found his chance to do something about this problem.

“When I had an opportunity to develop curriculum and educational philosophies, I put my own educational principles into play, particularly in the lives of black students,” he said. “When I had the opportunity to do more than just lecture in the classroom, I was very, very extremely passionate about that.”

Over the next two decades, until 1992, Hicks devoted his work to the academic world. He also earned his master’s degree in the philosophy of education at Cambridge College in Massachusetts in 1984.

In 1992, Hicks was offered a job as the director of community collaborations and program development at the New England Conservatory in Boston, a highly esteemed music school, which is where he eventually retired.

Since he was 11 or 12, Hicks had always had an interest in music, and he took piano and cello lessons through his teen years.

“My interest in music was always a deep and abiding interest of mine, even while I was at Drake,” he said.

Growing up in Boston, Hicks lived down the road from the conservatory, and on his way to the YMCA, he’d pass it and hear the music rumbling from the large building. He was always curious to see the musicians inside but never had the chance.

So when the opportunity presented itself in 1992, Hicks gladly took it. At the New England Conservatory, Hicks also worked in the humanitarian department and provided music instruction to students of all ages.

When Hicks retired from the conservatory in 2008, it was momentous. At his retirement announcement, the mayor of Boston was in attendance and proclaimed a “Calvin Hicks Day” in Boston to commemorate his incredible contributions not only at the conservatory, but also as an activist, a journalist and a revolutionary in African-American education.

In addition, in 2010, Hicks was awarded the Drum Major Award in Martin Luther King’s name from the Martin Luther King, Jr. Association due to his life’s work improving the unity and educational and communal environments for all people.

“What runs through all of my various activities is a consistent theme in all of my motives and purposes,” Hicks said. “That is to broaden the base of understanding and consciousness as much as I can to break down the divisions between communities and institutions, to be inclusive, to bring a certain kind of intellectual rigor to whatever enterprise I’m involved in and a certain kind of thinking that suspends our biases — to really look at what’s going on.”

Hicks said he is glad that he can look back on his career and know that his work brought change and made a difference in many lives.

But perhaps, he said, he can feel that he’s been successful by looking at the impact that others have claimed he made on their lives, such as the mayor’s admiration of his work, and through the institutions and universities that willingly adopted his philosophies.

Hicks still said he wishes and feels that he could’ve done even more.

“I certainly have pride to be of some value, not always successfully,” Hicks said. “I’ve made plenty of mistakes, but I certainly have tried to be of some value.”