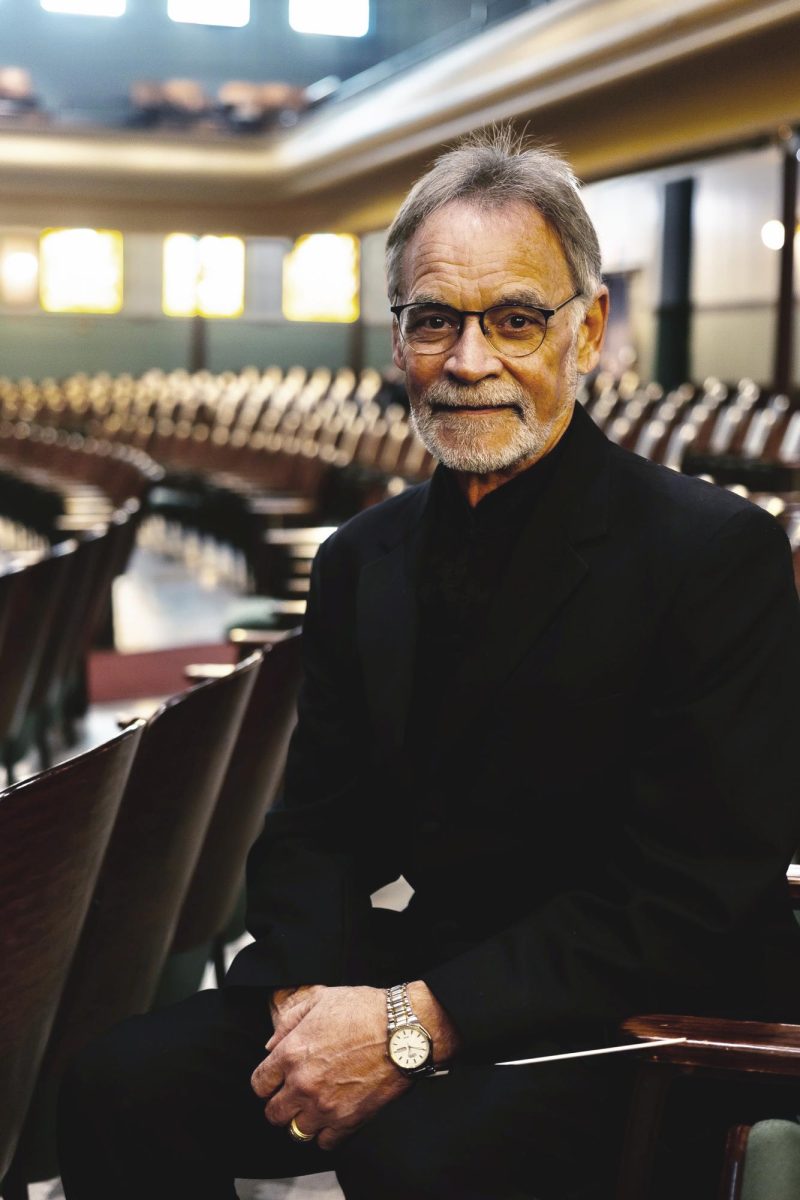

Photo: www.music.surfjan.com

Say good-bye to the banjo–and the 50 states.

Sufjan Stevens’ most recent album “The Age of Adz” (pronounced “odds”), is definitely something different for the young, Brooklyn-based musician. Stevens garnered a lot of attention back in 2003 for boldly claiming that he intended to write and record an album for every state in the union. The 50 States Project began with the release of “Greetings from Michigan: The Great Lake State,” a more minimalist approach when compared to his next feat.

“Come on Feel the Illinoise,” released in 2005 was a huge critical success demonstrating Stevens’ ability to write songs with big, lush orchestral arrangements juxtaposed with minimalist folk pieces that matched his whispery, emotive voice. All of this high-concept jibber-jabber worked pretty well for Stevens, resulting not only in a musical epic, but a whole hour and fifteen minutes of outtakes and extras released as “The Avalanche.” He managed to cram a career’s worth of work into one musical effort. Needless to say, he was a little exhausted and took a break.

During his public musical exile, Stevens did a lot of little experimental projects, including a music/film project about the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. He really loves places. All the while, gossip loomed about what state he would tackle next; guesses ranged from Minnesota and Oregon, to California and New Jersey. But Stevens was pretty much done, telling The Guardian in 2009 that he “had no qualms admitting it was a promotional gimmick.” After going through a musical existential crisis, Stevens embarked on a new path that freed him of the folksy, swelling Americana that characterized his previous albums.

The result was “The Age of Adz”–a swirling, electro, apocalyptic, prog-rock, Disney-esque…well, what can you call it? “Adz” bears only a shade of resemblance to the states’ records. Released near the end of 2010, it is Stevens’ first original studio release in five years. (That’s about 10 in music industry years.) All that time has certainly given Stevens time to clear his head, and he puts just about all of his ideas into the 11 tracks on “Adz.”

It starts out simply enough with the brief “Futile Devices,” a quiet little love song with layered guitars and piano—pleasant and standard. Then, immediately afterward on “Too Much,” it begins to sound as if Stevens has been playing tennis with the Flaming Lips, establishing an electronic orchestral sensibility that is consistent for just about every tune on the album. The swooping sound is all over the place, but in a good way. Drum machines kick out mechanized beats while synths glide through arpeggios next to big brass and string arrangements. It works both ways, really. At times the computerized sounds take on the quality of the organic instrumentation, and at others, it makes a whole string section sound like an army of robots from hell. Everything sounds dangerous and foreboding, like the soundtrack to a film about machines wiping out the human race. We’re not really dealing with geography, here.

Lyrically, however, the album is Stevens at his most personal. “Lover, will you look at me now?/ I’m already dead/ But I’ve come to explain why I left such a mess on the floor” (“I Walked”). By de-conceptualizing his work, Stevens manages to connect to the singer/songwriter inclinations that he established on “Seven Swans” and “A Sun Came.”

The only difference is that Stevens is dealing with more pronounced emotions—existential crises, death and, as always, matters of faith and spirituality, but on an angrier level than his previous albums. Plus, he doesn’t have to work in a line about Adlai Stevenson somewhere in the middle.

However, “Adz” is more lyrically forceful, if only for the manner in which Stevens surrounds his melodies. The chord progression to “I Walked” is pretty akin to “Flint” from his “Michigan” album. Stevens’ fans will have no real problem recognizing that these melodies are similar in style to his other songs. However, to say that everything is pretty intense on this record is an understatement. Hell, Stevens uses auto-tune at one point to take on the mechanical electronic quality of the music. Underneath it are rich, precisely choreographed choral arrangements. It never gets cheesy, although at times it gets pretty bizarre. In this way, Stevens succeeds in delivering an original album following a successful one, not getting stuck in that rut of releasing the same album every two years. If you’re expecting a polite little album with songs about Decatur, Ga., Chicago, or Detroit, leave those notions at the door. As Stevens puts it in “I Want to be Well”: “I’m not f***ing around.”