Almost a hundred years after the first duck stamp was sent out to post, on Sept. 15 to 16 Drake University hosted the contest to decide next year’s stamp artwork. The stamp is required to hunt wildfowl, and 98% of the money goes towards wetlands or grasslands across the nation.

The contest took place in Parents Hall in Olmsted Center. On Olmsted’s upper floor was a gallery of the eligible stamps, an auction with duck stamp-related items and various tables.

One table sold duck decoys, painted wooden ducks that hunters use to lure live ducks.

“I don’t hunt. I just like the construction and art of them,” Todd Rozendaal, who ran the stand, said. “They’re really just sculpture to me.”

He’d brought a pintail duck decoy to the contest, originally found along the Mississippi River. Rozendaal collects mainly from Midwest auctions, flea markets and anonymous painters. He got into decoy collecting two years ago, having run a sports collectibles store when he learned about the craft.

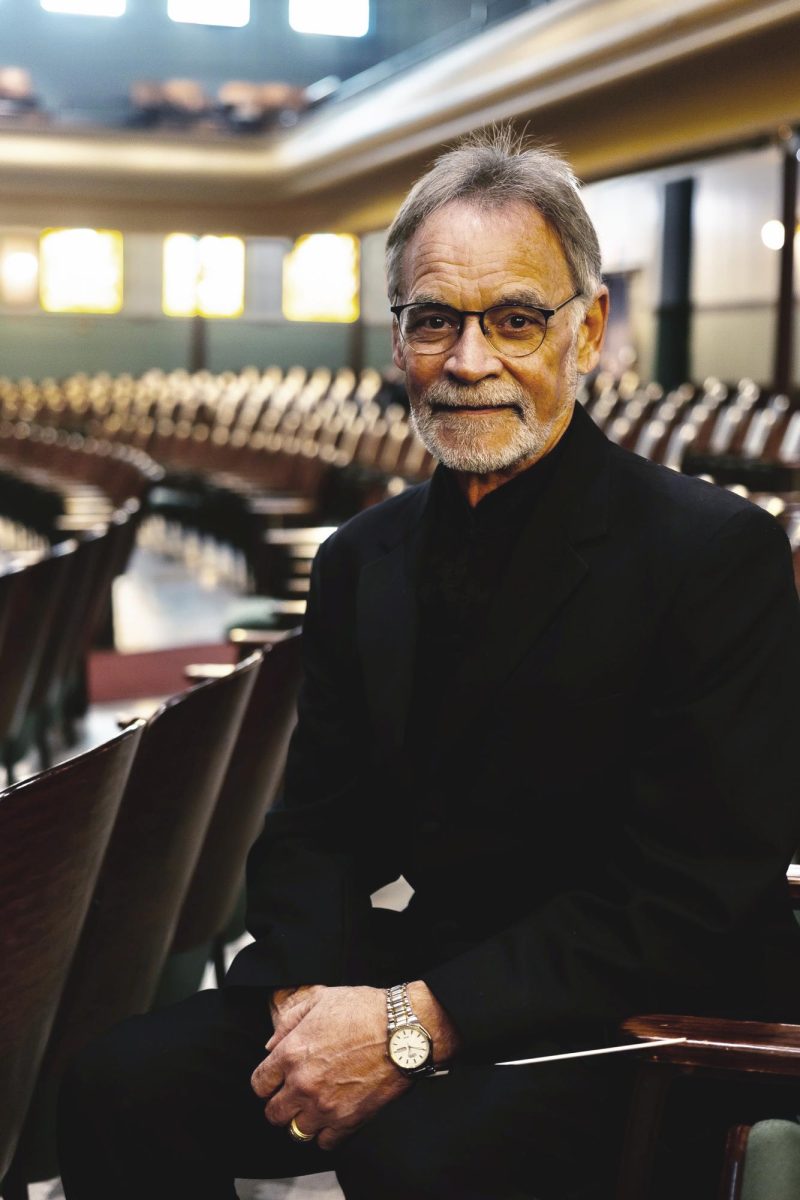

Neil Hamilton, a Drake emeritus professor of law and director of the Agricultural Law Center, has been involved with the duck stamp since the Darling Institute was first introduced to Drake over a decade ago. Hamilton has retired since the idea originated but spent time at the contest promoting his books about the environment.

“It’s going to bring to campus a large number of people who otherwise would not have come to Drake, a broader array of people from the nature community,” Hamilton said.

Sam Houston Duck Company from Houston, Texas, came north to advertise their business.

The company sells primarily to collectors, filling online orders and hosting auctions. Rita Dumaine originally sold other stamps before meeting her now-husband, who hired her to work for his company. Dumaine enjoys dealing with the collectors and looking at the art on the stamps.

“Going to the duck stamp contest is like having an MTV backstage pass to everything cool about duck stamps,” Dumaine said.

Dumaine and her husband have judged both the federal and junior duck stamp contests.

The Junior Duck Stamp contest is a state-by-state program where students learn about wildfowl and create a duck stamp of their own. Each state’s winner moves on to the federal contest, and the winner is printed at the same time as the federal stamp.

“It’s a wonderful program for them to get in touch with conservation,” Alyssa Lu, junior duck stamp coordinator for Iowa, said. Lu ran the program’s booth.

Besides coordinating the junior duck stamp contest in Iowa, Lu is a Visitor Services Specialist at De Soto Wildlife Refuge, having only recently started in the duck stamp coordination position.

“My favorite part is honestly just seeing the artwork and the creations people can make,” Lu said. “It’s amazing to see what their mind can create and how they can bring that to life on paper.”

This year, all the judges were women, a first for the contest. Judges Gail Anderson, M.J. Davis, Becky Humphries, Rue Mapp and Karen Waldrup selected the winning stamp, while Jennifer Scully served as backup.

Mapp, founder and CEO of Outdoor Afro and the Black Heritage Hunt, grew up in a family of hunters and fishers and is a duck hunter herself. Her organizations focus on getting people outside and highlighting Black conservation history. Mapp has a background studying art and viewed this as a combination of her two major interests.

Mapp said she was enthused to be part of the competition, seeing it as a “full circle moment.”

“It means that there’s going to be the support for places that people can go and enjoy watching ducks or hunting ducks in perpetuity,” Mapp said.

The judges spent two days deliberating in Parents Hall. Only the third-place award resulted in a tie — the winner was decisive.

Chuck Black, this year’s winner, has been entering the contest for over eight years but knew about the stamp since he was a child. Growing up in Minnesota in a family of hunters, he appreciated the art on the stamps that gave his family permission to hunt.

“It just became an obsession of mine. I took to artwork and loved to draw,” Black said.

Black and his wife traveled to their local wildlife refuge to take reference pictures of the ducks prior to the announcement of which species would be eligible. According to Black, every day, the same Northern Pintail sat in the nearby wetlands. On his final day taking photography, the drake stood still long enough for Black to get as many photographs as he needed.

“Right on cue it landed near us,” Black said. “When the pintail was eligible, I had to create from that experience.”

According to Black, he recognized that he was “onto something” with this year’s entry but didn’t get his hopes excessively high.

“I’m still in disbelief. It’s something that’s really hard to grasp for me right now. It’s been overwhelming, and I feel so blessed,” Black said.

This year, he’ll be touring with the stamp to promote the federal duck stamp program at various conservation gatherings. Black will not be able to enter the contest again for three years but is eager to “get back out on the water.”

The artist behind the first duck stamp and the program’s inventor, Jay N. Darling, passed away in 1962. Darling worked as a cartoonist for the Des Moines Register and headed the U.S. Biological Survey, which later became the Fish and Wildlife Service.

The original stamp was not meant to be the final design. Darling, for the benefit of Bureau of Engraving employees, sketched a preliminary design, which they took for etchings for the stamp.

“I could have murdered Colonel Shelton and all the Bureau of Engraving personnel, and every time I look at that design of the first duck stamp, I still want to do it,” Darling said in an interview available through the Darling Center.

At the time, distribution was difficult since few post masters knew what the stamp was.

As of today, the duck stamp has saved over 5.7 million acres of habitat for ducks and raised over $800 million for conservation.