This article discusses graphic material related to the Holocaust

History is more than just a subject in school where you learn about the dead — rather, it is a subject that is defined and created by humans and their actions. While time continues to move on, the people from the past stay with it, but historians attempt to remember each and every person who was involved.

Gathering evidence or accounts of each survivor’s story is a dilemma that humans are experiencing right now, as the youngest generation to have survived and witnessed the atrocities of the Nazis personally are dying. This rings especially true for those in Iowa with the passing of its last known Holocaust survivor, David Wolnerman, on Sept. 4, 2023.

Wolnerman was born in Poland on May 9, 1927, where he grew up with his father, mother, older brother and two older sisters. For the beginning of his childhood, he remembered he and his family being harassed for being Jewish.

1939 was devastating for him not only because of the German and Soviet Union invasion of Poland that September but also because of his father’s death that spring. After the invasion, Wolnerman was deported to a labor camp. He saved his life by lying about his age, saying that he was 18 instead of 13, an age that would have resulted in his being killed.

Within the first six months of his time at the Auschwitz concentration camp, he contracted typhus. He survived and was then transferred to other concentration camps, including Birkenau. Wolnerman was at Birkenau for two years and was transferred to Dachau and then Muhldorf, after volunteering to clean up the rubble from the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

After witnessing numerous displays of human cruelty in the camps, Wolnerman reported feeling “emotional numbness.” These cruelties included piles of corpses, cruel guards, the constant smell of burning flesh and castration.

Wolnerman was finally liberated by American troops in Muhldorf and spent the next four years living in Dießen am Ammersee, a part of Bavaria, Germany, that was under American control at the time. He met his wife Jennine, a fellow survivor, in a displaced persons camp and also reunited with one of his sisters and cousin. He and Jennie married in his hometown before emigrating to Cleveland, Ohio, and later Gary, Indiana, to be near Jennie’s surviving relatives.

Once Wolnerman’s heart problems forced him to retire from his job in the grocery business, his sons convinced their parents to move to Des Moines to be near them as they finished studying pharmacy at Drake. Both David and Jennie, who passed in 2016, spent the rest of their lives in Des Moines.

As he adjusted to life in America, Wolnerman struggled to talk about his experiences — a common struggle for Holocaust survivors. As his children grew older, Wolnerman joked that the number on his arm was the phone number of his ex-girlfriend.

The “work, work, work” mentality ingrained into his head at the camps never left him. Wolnerman worked “eight days a week” to give his children something he was never able to receive — an education. However, once other survivors began telling their stories, Wolnerman did the same. Wolnerman gave numerous interviews about his experiences, as early as 1985. One message that Wolnerman gave was, “you have to forgive, but don’t forget.”

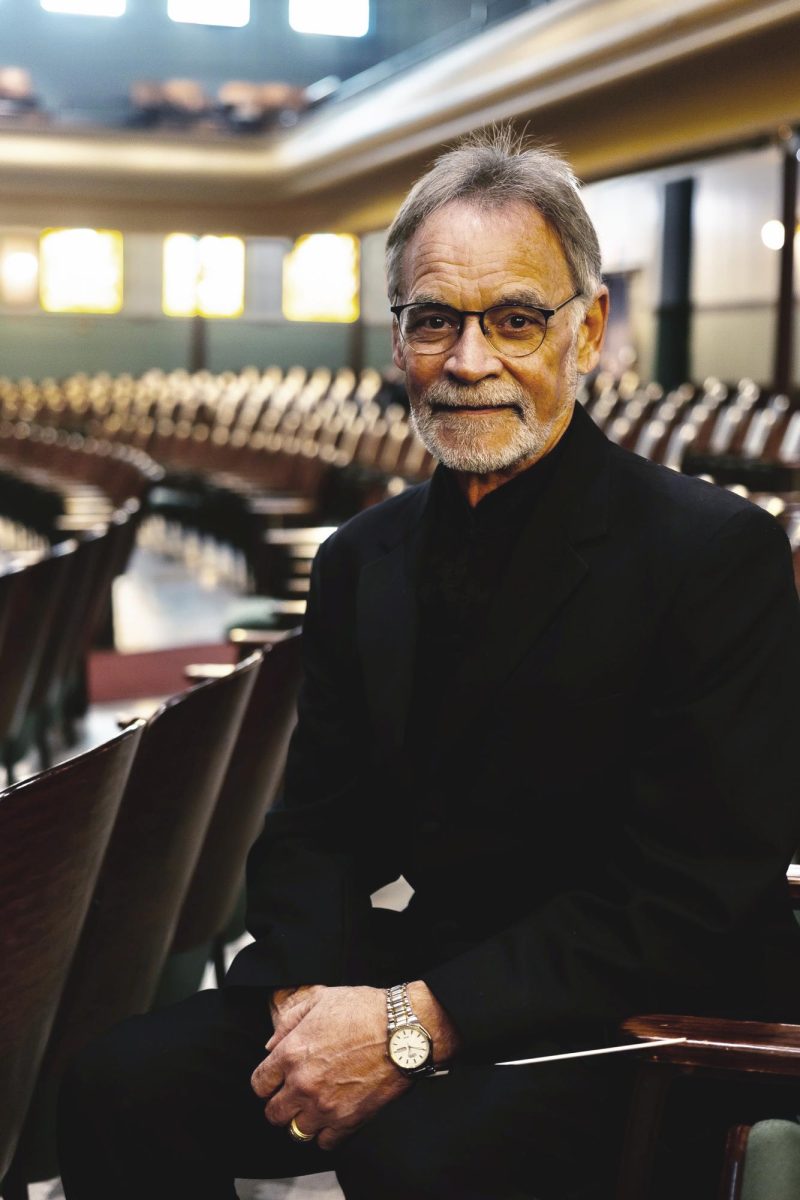

When the question of teaching and remembering the past comes up, the answer is never clear. However, something that makes it easier to understand, according to Drake University Emerita professor of advertising Dorthy Pisarski, is “having that personal connection to survivors…that way it does not become another moment in history.”

Pisarski, the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, is on the other side of Wolnerman’s story. Growing up, Pisarski remembers her father “hardly talking about [his experience] if at all.”

“There had to be the right moment to prompt him to say something…by the time I realized how important [hearing about his experience] was, he had gotten older and was less willing to talk about it…But hearing from my aunt about their parents’ reactions to his disappearance, it was enlightening.”

As time has progressed, history has revealed the stories of survivors’ “nuclear families,” making studies much more complex and personal. Pisarski understands that not everyone will have a personal connection, but in order to teach the past, it would be helpful to “bring in a speaker who can make that personal connection.

“[Each speaker] brings in a different perspective and angle to teach the Holocaust [that might resonate with someone] and from there, make a connection with a survivor,” Pisarski said.

Drake University is familiar with Holocaust remembrance. Drake has a course called Holocaust and heritage where students travel to Germany and Poland.

Beyond the course, Pisarski “worked to bring Holocaust education to campus. [There were] three times [Pisarski and her collaborators] brought in speakers from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C., two times we brought in survivors with their books, and just before COVID-19 started, we put up a poster display on a loan from Washington D.C., but then COVID hit, so unfortunately not many people saw the posters.”

With these initiatives, Pisarski sought to elevate Holocaust awareness at Drake.

“I was always impressed with the turn-out that these events created,” Pisarski said. “We got good sized audiences.”

However, these initiatives took place before the pandemic, when current Drake students entered the school.

“I can’t really think of much Drake has done,” Rachel Shugarts, a senior history major, said. “It’s not exactly like Drake doesn’t care. I just don’t think they have mentioned the Holocaust very often since I’ve been here.”

While teaching and remembrance are crucial not only to create history curriculum, Shugarts adds that studying history could create a more just world.

“History should always be remembered,” Shugarts said. “We should always be looking to the past to create a better future. If history is not taught, then we have to reinvent the wheel, causing a considerable amount of struggling and suffering all over again. If history is taught and learned, then this will be prevented.”