From Sept. 15 to 16, Drake’s name will have a double meaning. Paintings of ducks, or drakes, as the males are known, will be hung in Olmsted Center to be judged to decide the next federal duck stamp.

“Most of the duck stamp funding is used to conserve waterfowl habitat like wetlands and the surrounding grasslands. It’s a great way to include a different set of people in conservation than we usually have,” said Suzanne Fellows, Chief of the Fish and Wildlife Service Federal Duck Stamp Office in Arlington, Virginia.

The duck stamp is an official document that grants migratory hunters permission to legally hunt and purchasers access to wildlife refuges. It is, however, not a stamp — at least, not a postage one. Invented by Iowa resident Jay N. Darling, the duck stamp was originally a way to limit rampant wildfowl hunting.

98 cents to every dollar from a $25 stamp purchased goes towards wetlands conservation. Over six million acres of wetlands have been conserved through the $1.2 billion the stamp has raised.

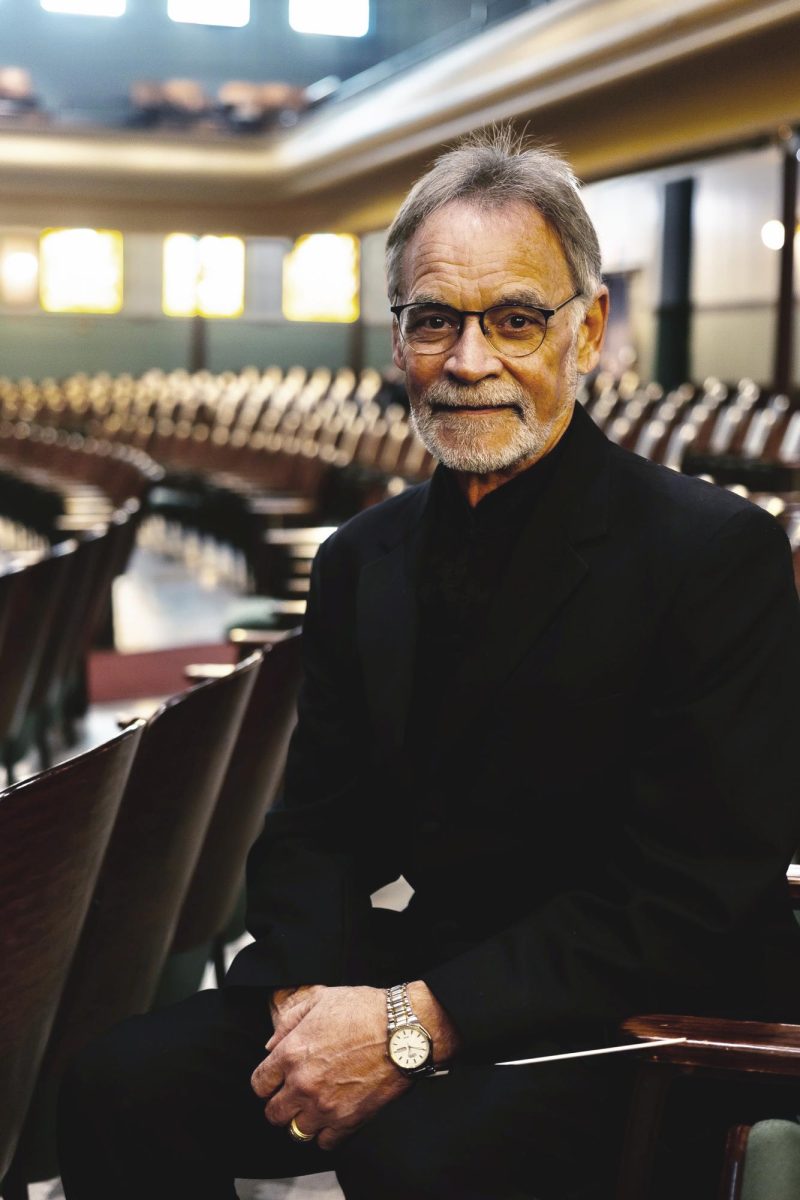

“We continue to see the impact of what the duck stamp represents. I’ll know that our team and our institution played a part in that legacy of conservation,” said John Smith, Vice President of University Advancement and senior administrator representing and supporting the steering committee for the contest.

Darling advocated strongly for government funding for wildlife restoration and research on duck hunting statistics. The year the stamp was introduced, a hunters’ conference debated having a ‘closed’ season, or a season with no hunting, due to the decreases in wildfowl that excessive hunting caused.

Darling’s advocacy for conservation went beyond the stamp. Keith Summerville, head of the Darling Institute, an organization at Drake that works on improving access to food and heath care in rural communities, described Darling as having “a career that spans time in the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, and in a role that [would] ultimately produce the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.”

One reason that Drake is hosting the contest is its connections to Darling. Darling worked as a cartoonist for the Des Moines Register under Gardener Cowles — the namesake of Drake’s undergraduate library — and received an honorary doctorate from Drake.

According to Sam Koltinsky, chairperson of the 2023 federal duck stamp contest, Darling was also a judge in the Drake Relays and advocated for Drake University’s future expansion. Cowles Library currently has an exhibit dedicated to him, and the archives has a collection of his papers.

“What’s really interesting for us is that we, a lot of times, are looking for connections between our collections. Darling appears in some of our other collections as well,” said Hope Bibens, the director of university archives and special collections. Bibens highlighted the connections between the Darling, Cowles and Harlan collections.

Koltinsky advocated for the contest to be held at Drake beginning in 2016 and managed to schedule it for the fall of 2020. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, it had to be postponed to 2023.

“Because of his connection to Des Moines and to Drake, Sam Kotlinsky always had a dream of bringing the duck stamp competition back home to central Iowa,” Smith said. “Through Sam’s advocacy, the university’s positioning and then through the creation of the Darling Institute, good synergy brought the opportunity to us.”

Koltinsky was surprised when he learned it had never been held in Iowa. He attended other contests and began advocating for the contest to be held in Des Moines, a place he thinks is part of the “footprint of Darling.”

The first duck stamp, created in 1934, was not selected through a contest, but by accident. Darling drew an idea of what he wanted the duck stamp to look like on a piece of cardboard, which two officials took to be used as the design. The art on the stamp was commissioned until 1949, when the first contest was held.

“It’s just a way for more people to be involved in the process [and] contribute their artwork to conservation,” Fellows said.

Until 2004, the contest was held in Washington D.C., but since then it has been traveling around the country, especially to university campuses.

“I like having a contest at a university, where we can attract a new generation of people — people who might not be familiar with the duck stamp — and just show them this opportunity,” Fellows said.

Entering artists must be over 18 (artists under 18 can enter the junior duck stamp contest), can only enter one piece, must send a fee of $125 and must have submitted it by Aug. 15.

The contest includes three rounds of judging to slowly eliminate entries and determine the year’s duck stamp. Five judges and one alternate judge — a judge chosen in case one standing judge is unable to perform their duties — look for anatomically correct artwork of one of the eligible species in its natural habitat that can be reproduced on a stamp.

This year, the eligible species are the Snow Goose, American Black Duck, Northern Pintail, Ring-necked Duck and Harlequin Duck.

Artist Kira Sabin chose to paint the Northern Pintail duck.

“They’ve always been a favorite of mine. They’re a favorite of a lot of people. I just think they’re beautiful ducks. I love the brown color and, of course, their cool long tail,” Sabin said.

Sabin has been entering submissions to the contest since 2019, when her grandfather, a hunter, first told her about the contest. This is her first year in person due to the pandemic that made it impossible to attend in person.

“I am so thrilled to meet other people who enter [and] other people who just want to support it. I just so desperately want to see the works of other people in person,” Sabin said.

There is no monetary reward for winning the contest, but the winner tours the country with their stamp and helps to promote conservation and can refer to themselves as having won the contest on all future works. The artist’s design is used as the next federal duck stamp beginning in June.

“My goals are always just to improve from the previous year. I just want to know that I’m moving forward,” Sabin said. “And obviously, I would like to win at some point in my life. That’d be the main goal.”

The contest spans two days, during which Drake will be screening films related to the contest and its history. On Sept. 15 at 2 p.m. in Sussman Theater, “America’s Darling” about Darling’s life will be played immediately followed by “Wings over Water.” That same day from 3-4:30 p.m. in the Upper Olmsted Gallery, former CEO of Ducks Unlimited Dale Hall will be signing his book “Compelled,” which is about conservation through the eyes of a young biologist.

Throughout the event, Drake will be hosting exhibits honoring duck stamp winners Maynard Reece and Robert Hines and displaying Darling’s 1926 sketchbook.

One of Smith’s goals was to make the event useful for different majors and to honor Darling’s legacy as a “renaissance man.” This will include, according to him, journalism and environmental science students being brought by classes to the contest, opportunities for fine arts students and students in the public democracy scholars program.

“We hope through mostly organic engagement that students find their own ways to have exposure to the competition, engagement with artists, policy leaders and guests and through their own observations and interactions, in the spirit of Drake’s students taking ownership of things, will find their own opportunity to benefit from Drake hosting the competition,” Smith said.

Alanna Wuensch, a student intern at the Darling Institute, has been working on the duck stamp contest since her junior year. She worked primarily on orienting and connecting attendees and had the opportunity to speak on a panel about the event.

“It helped me in so many ways as an individual and as a potential leader in just growing me in so many other ways that was never expected,” Wuensch said.

Wuensch added that, especially as a student, she hopes that other students learn about Darling and his impact from the event as she was impacted by his legacy.

“He created comics. He was a conservationist, he was a journalist and he did all these things. He was an advocate first and foremost, and he brought up some of the things that I think will be a good reminder for people going forward,” Wuensch said.

The contest and the Darling Institute are part of Darling’s legacy. The Darling Institute works on projects that improve standards of living in the rural Midwest and encourages people to learn about Darling’s work.

“I feel that this is an event of a lifetime, ” Koltinsky said. “I think that this can be an event of hope and inspiration, and the world needs that.”