The first thing Kristine Bunch did after being released from prison was to go to a nearby park, take off her shoes and walk barefoot on the grass for the first time in 17 years.

Recalling this day almost seven years ago, her voice, which had been soft-spoken up until this point, gained a certain amount of joy revealing the impact that day had on her.

After being wrongfully convicted of setting a fire that took her three-year-old son’s life in 1995, Bunch underwent many hardships that most could not withstand. During her trial, Indiana state arson investigator Brian Frank said the fire in Bunch’s home was started by an accelerant but could not identify the substance.

Bunch said she knew even before her own court-appointed public defender ever spoke that she was going to be found guilty in her trial, as the prosecutors were portraying her as a “loose woman that did not want a kid.”

“I mean, in that moment, you’re trapped – you have to depend on somebody else to speak your truth, to portray who you are,” Bunch said. “So I couldn’t ever get up and speak my truth. I had to trust that the person that was, you know, on my side was going to show them who I was. And so that’s a hard position to be in when you have to place the rest of your life in somebody else’s hands. So you just hope this lawyer you’ve got is going to do the right thing.”

In 1996, Bunch was found guilty by a jury and was sentenced to 60 years for murder and 50 years for arson.

She didn’t stop fighting for her case and had to go to extreme lengths to even get the information necessary to prove her innocence. Bunch said she had to be her own advocate in order to get a lawyer to look at her case file.

She remembers sending out hundreds of letters “begging people” for help, and most were ignored. It was only when she discovered things on her own about her case and highlighted what could help that she started receiving help.

“When I read the [National Fire Protection Agency 921] manual, I couldn’t check it out, it was a reference material at the public library. So I had to pay 10 cents a copy per page and I could only get 10 pages per week. So it took me a while to get that manual,” Bunch said. “And so if [prisoners] don’t have access that they need, to the research material to law books, it’s really hard for them to advocate for themselves and a huge portion of people that are locked up in our prisons [have] substance abuse issues, mental health issues, they don’t have formal education [and] there are cultural and language barriers…so they’re at a disadvantage.”

On March 21, 2012, the Court of Appeals of Indiana reversed the conviction and on Aug. 22 Bunch walked out of the Decatur County Jail. Prosecutors dropped the charges against her later that year, meaning no new trial would take place.

And 17 years, one month, and 16 days after her arrest, Bunch was a free woman.

Initially “really excited” after hearing about her reversed conviction, Bunch said the reality of her situation set in after realizing she had “no money”, “no job” and “no home.”

“It’s like this mountain settles on you in the fear because you don’t know where to go, who to turn to, you know, ‘How do I get the necessary documents to prove who I am, even though I’ve been on the six o’clock and 10 o’clock news every night for a couple of days and prove that I am this person and get my license?’” Bunch recalled feeling. “‘And how do I reestablish and how do I build credit?’ So it’s like you come out with this clean slate and you’re trying to do everything all at once and you realize there’s some things I’m just not going to be able to do because I have to focus all my energy over here and rebuilding my life.”

Since leaving prison, Bunch has become an advocate for exonerees, founding Justis 4 Justus, a non-profit organization that helps exonerees build a community of support. She is also the outreach coordinator for Interrogating Justice, a non-partisan think tank that tries to illuminate the ways in which the justice system fails short, where she travels across the country telling her story.

Through her advocacy work, Bunch travels around the country to talk to people and work with organizations like the Midwest Innocence Project, a non-profit organization that helps provide resources for exonerees in the Midwest. Through her work, she met Erica Nichols Cook.

Founded by Nichols Cook in January 2020, the Drake Wrongful Convictions Clinic provides students the opportunity to learn about post-convictions work.

The clinic is part of a collaboration with the Drake Law School and the Iowa State Public Defender, whose Wrongful Conviction Division works with The Midwest Innocence Project.

Drake’s Wrongful Convictions Clinic recently became a member of the Innocence Network, a non-profit organization fighting wrongful convictions.

“It’s an important recognition that we are doing the work right and it gives us access to other network member organizations to partner with them on cases, to get their research, to go to conferences with them and learn how to propel our cases forward,” Nichols Cook said. “And the Innocence Network, the Innocence Project, they do more policy work than I can and so it’s a way for Iowa [to be] represented in those greater policy outreach plans.”

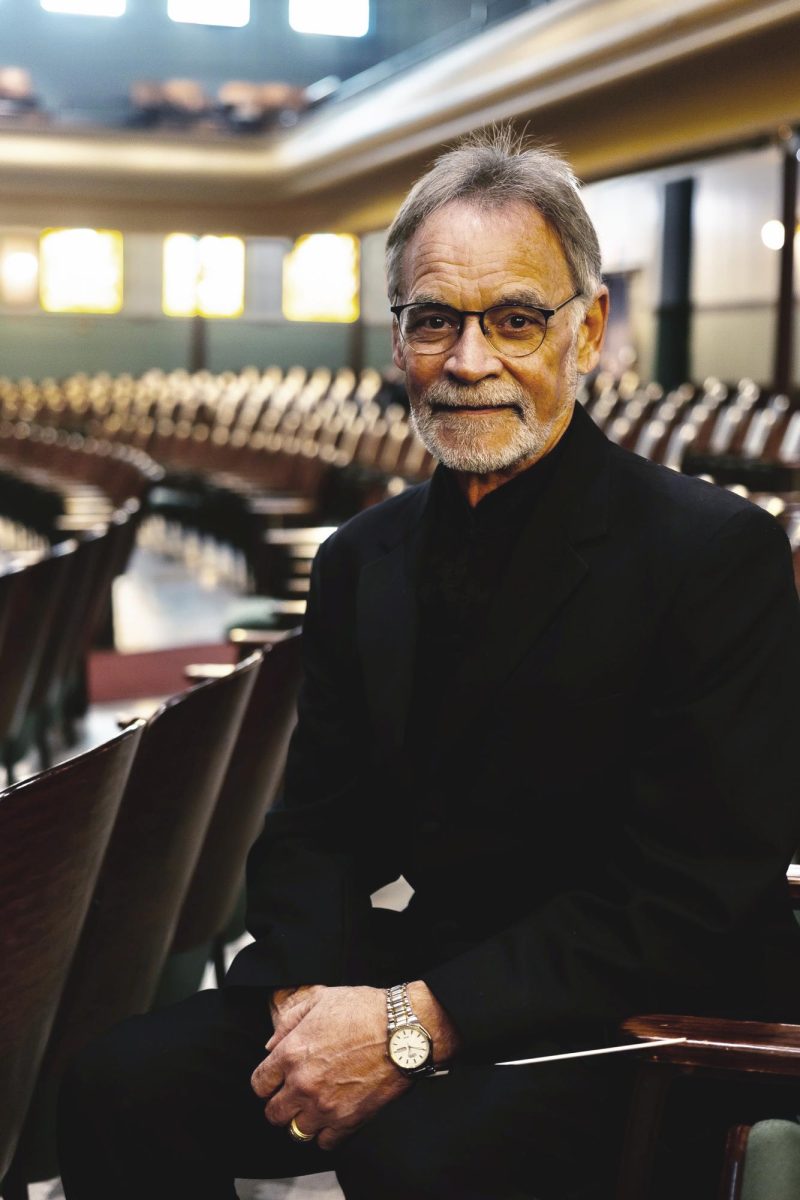

Nichols Cook serves as the clinician in residence at Drake’s Clinic and is also the Director of the Wrongful Conviction Division of the Iowa State Public Defender.

Nichols Cook graduated from Drake Law School in 2009 and worked at the Criminal Defense Clinic. After working as a public defender at the office of the Iowa State Public Defender, she said students in the two-credit internship program didn’t get a lot of post-conviction experience, as cases can take “six to 10 years to resolve.”

Enrollment at Drake’s Wrongful Convictions Clinic is open to students who have done at least three semesters of law school and can take four to six credit hours. Students can also receive a student practice license, allowing them to help in court and depositions “really build a better relationship with the client.”

Students get assigned a case that is in the petition phase or is getting ready to be filed and work with a team, including the local counsel from that county. From there, students assist with anything related to the case, from collecting records to helping prepare oral arguments to interviewing witnesses. At the end of the semester, students put together a presentation about their case, debating whether or not it’ll be successful.

“So there’s a presumption of innocence when you go to trial and historically wrongful convictions happen in big cases where there’s public scrutiny, and we know from the over 3000 exonerations across our country that science has changed dramatically. That DNA has proven confessions are false, they’ve proven that matching hair or shoe prints is not reliable, and we have a lot of cases in Iowa involving those types of things,” Nichols Cook said. “And we only have 16 exonerations in Iowa [since] 1989, and we have no DNA exonerations. So we know there are innocent people in Iowa prisons.”

Sometimes the issue is that defendants do not get represented as well as they should.

“We also know that every person deserves a fair trial, and they deserve competent legal counsel. Our Iowa statute says that they get an attorney on post convictions. But sometimes that attorney does not have the time or the resources to investigate their case for them,” Nichols Cook said. “So it’s really important for students that are going to be lawyers, to know how to investigate a case, to know how to build a trusting attorney-client relationship, and…how to be critical and skeptical of evidence.”

Bunch recently gave a presentation to Drake law students working at the Wrongful Convictions Clinic. She said she thinks people getting to see someone like her, see “a real person that has suffered through” a wrongful conviction humanizes it.

“They recognize that when they are dealing with any client, they could be a person just like me. So I think it really bridges the gap for them,” Bunch said. “Because lawyers are in many ways, like geniuses, you know, they are sitting there looking at facts, and weighing out, ‘How can I make these facts fit into law? How can I argue this?’ And I don’t think they often take a look at their client and realize how much a client can share with them, how much insight they can give them into what they need to investigate. Because they don’t always take the time to dig through the emotions.”

Nathan Sandbothe, a recent graduate of the Law School, worked at the clinic for two semesters last year. Sandbothe said he almost tried to quit the clinic after a few weeks as he was unsure about committing to a different kind of law during his last year at Drake. However, he is glad he went through with it and found it “really rewarding.”

Sandbothe said Nichols Cook prepared him well in post-convictions work, so much so that he has listed it as an area of interest when looking for jobs.

After working at the Wrongful Convictions Clinic, he found his perspective changed, but not for the better.

“I don’t think I realized the extent to which our system is kind of broken…I acknowledge that our criminal justice system had big issues [prior], but I don’t think I understood how broken it was for people who are incarcerated, and just the sort of hoops that they have to jump,” Sandbothe said. “It’s just the degree to which some of these people are just truly forgotten. Even when some of them do have very strong claims of innocence and things like that, there just aren’t a lot of options…and the standards we set are extremely high for them to prove their innocence.”

Bunch thinks it’s important for law students to be doing post-conviction work because there is a lack of resources and attorneys in the field.

“The Innocence Project estimates that 10% [of prisoners] all across our country [are] innocent. I’m pretty sure the number is higher than that after being in prison,” Bunch said. “So when you think about all those people, how many letters come into attorneys and clinics all across this country, and they’re taking less than 1%. It’s important for students to step up because their research, their help enables that attorney to do more and make a difference in more lives.”