“Des Moines goes under quarantine today,” the front page of the Des Moines Register read. Similar headlines have popped up in the news recently, but this one is actually from 1918.

Nearly one century later, the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic returned to many people’s minds as a parallel to the coronavirus pandemic. After infecting one-third of the world’s population and killing 50 million people worldwide, this crisis became a reference point for the current one.

What happened in 1918?

One trait these two pandemics share for certain is how they began: travel. In 1918, World War I was in its last year. But the world didn’t know that, nor did they know that the year would bring an event deadlier than war.

“By 1906, the United States had been crisscrossed with over 240,000 miles of railway. All types of ships crossed the Atlantic and Pacific oceans regularly … By 1918, the world seemed far smaller and more connected than it had been at any time previously in history. The world stage was set for the flu pandemic of 1918,” reads a document from the Glen Ellyn Historical Society in Illinois.

Spanish flu was more deadly than past influenza strains; it targeted younger adults, which was atypical of flu viruses, and was often incurable. In Des Moines, many in that demographic were at Camp Dodge miles away from the city center waiting for their call to war. According to the Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs, around 8,000 troops were infected at the peak of the flu’s spread, and in the span of two months 702 soldiers died.

At the time, Drake University was home to its own Student Army Training Corps that prepared male Drake students for the war. From September to the end of the war in November, 102 soldiers lived in the men’s gym, which was converted into housing barracks. As reported by the Times-Delphic on Oct. 8, 1918, the men quarantined in these barracks for two weeks, not due to the flu but per standard army protocol. However, that day the paper also reported 25 men were taken to the hospital, and confirmed on Oct. 11 that they had Spanish flu.

A quarantine on the city of Des Moines, including Drake’s campus, began on Oct. 10. Similar to the March business closures related to COVID-19, the Board of Health in 1918 closed schools, churches and other gathering places and residents were asked to stay home if they had symptoms of Spanish flu, according to an essay on Des Moines published by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine. As both of these diseases affected the respiratory system, many of the ways people protect themselves from COVID-19 were also used in 1918.

“They did wear masks back then too, and washed their hands,” said Claudia Frazer, professor of librarianship and director of university archives and special collections at Drake. “I’m not sure how much they did with social distancing in terms of six feet, but they did wear masks.”

At first, residents were not specifically instructed to social distance in 1918, but it occurred naturally when the Board of Health instituted a mask mandate in all public places on Dec. 2 following a resurgence of cases in November.

“Across the city, theaters and movie houses reported half of the usual attendance. Many Des Moines residents, it seemed, so disliked wearing flu masks that they preferred to remain at home rather than to don one,” the University of Michigan essay said. “Bending to the will of the people and business interests, and with the support of physicians who (correctly) argued that gauze masks did little to prevent the spread of influenza, the Board of Health revoked the order on December 4 and once again made the wearing of flu masks voluntary.”

Despite the willingness to stay home, the highest single-day case count was 500 on Dec. 4, the day the mask order was removed. Officials implemented social distancing guidelines until Dec. 16, closing businesses with poor ventilation and limiting others to half capacity. Although these pandemics exist eras apart from each other, residents and city officials ultimately fought the same enemy.

What’s changed?

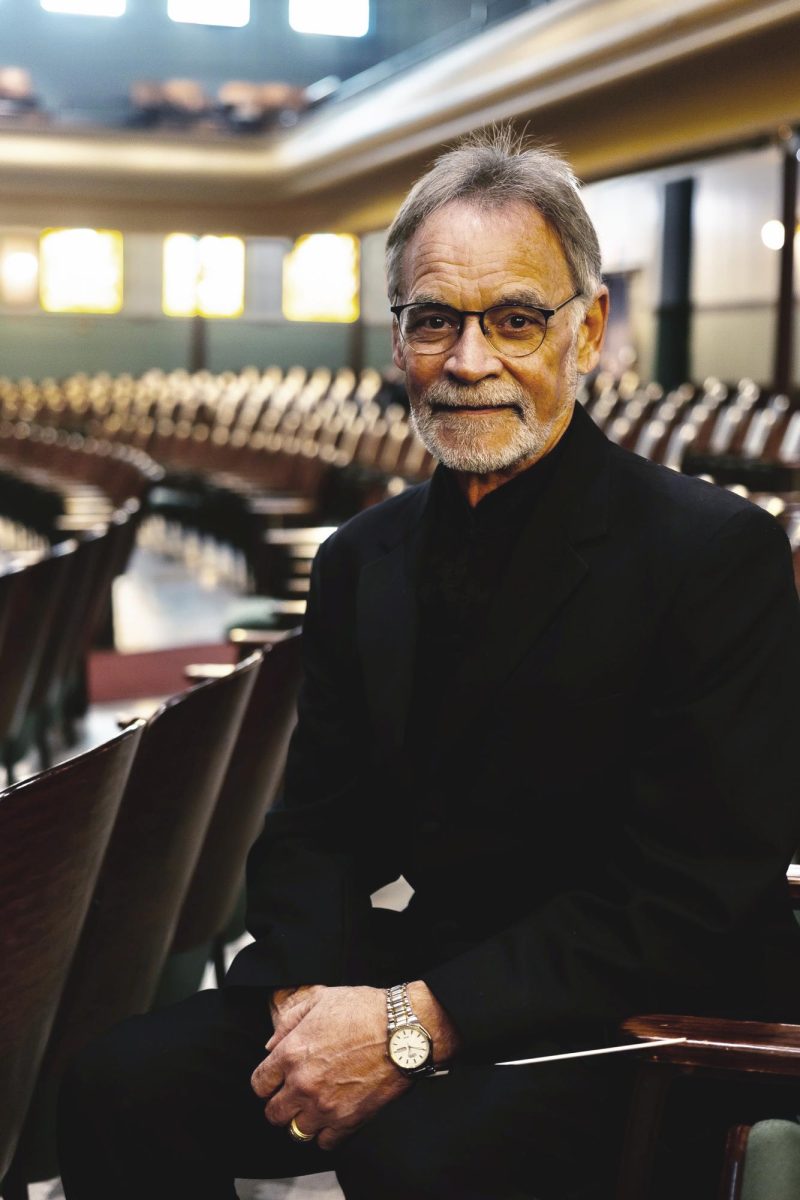

Ninety-eight years after the Spanish flu hit Des Moines, the world has changed greatly in terms of technology, information and culture. Milo Plavec, a Drake University alumnus familiar with the school’s history, highlighted how the COVID-19 pandemic has been largely politicized in comparison to the Spanish flu.

“It seems like the reactions are entirely different,” Plavec said. “Right now there’s a lot of politics involved. Back then, there didn’t seem to be any politics involved. People took precautions all over the country. There’s similarities with distancing and wearing masks, but it didn’t seem like there was any opposition to that like some people do now.”

Des Moines fared better than other cities in the state, producing a smaller effect on Drake’s campus. The Oct. 11 issue of the Times-Delphic reported the conditions of the University of Iowa in Iowa City.

“The State university of Iowa has been affected much worse than Drake by the ‘flu.’ Over 200 cases have been reported,” the paper read. “The law and engineering buildings, part of Currier hall, the girls’ dormitory and several frat houses have been turned over for isolation hospitals. The campus is guarded day and night, and passes are required for entering or leaving the campus.”

Despite mass compliance with flu precautions, Drake’s response to the 1918 pandemic was relatively small. Following the city-wide quarantine, campus life had largely returned to normal. Drake President Arthur Holmes addressed students for the first time since their return to campus without once mentioning the pandemic.

“This was November 1st. This was at a pep rally, after the school reopened they had a pep rally,” Plavec said. “A whole bunch of people showed up and they were cheering as if nothing happened. In his speech he didn’t say anything about the flu or the school being closed at all, or saying welcome back. He never even said anything about it.”

Pandemic response at Drake in 1918 was limited largely due to a lack of information.

“Certainly the 1918 administration kept in mind the same goal of health and safety for the community, but there was much less scientific information available,” said Provost Sue Mattison. “However, the death rate from the 1918 pandemic was much greater than for COVID-19 because the world didn’t have the same tools and modes of communication we have.”

For this reason, Mattison said, the Spanish flu response was not used to inform Drake’s COVID-19 response. Unlike in 1918, Drake now has access to knowledge of disease transmission and case tracking, as well as concrete plans for isolation and quarantine procedures.

“Our focus is on protecting the health and well-being of students, staff, faculty and the neighborhood,” Mattison said. “We rely on basic principles of pandemic response in general, and evidence-based medicine specific to SARS-CoV-2 that we consider as we make daily decisions.”

Preserving COVID History

While Drake did not use information from the 1918 flu to inform their pandemic response, there are still lessons to be learned. Frazer and her peers are in the process of collecting information from students on their thoughts during the pandemic in order to preserve them for future generations.

“We are trying to hook up parts of our collections, for example what we get about COVID-19, we’re trying to hook that up with the pandemic of 1918,” Frazer said.

Last semester, adjunct history professor Megan Sibbel asked her students to create oral histories and write diary entries to document their thoughts over the past few months. The library is in the process of collecting and consolidating this information to present a portrait of student life during the pandemic.

“What we’re working on now is a website that will have these oral histories on it as well as little diary entries that these students wrote on what their thoughts were at the time,” Frazer said.

For today’s college students who are in the middle of one, a pandemic seems like a rare, once-in-a-lifetime event. But by turning back just a few pages, the past shows we are no stranger to the danger of disease. Whatever the stage — battling a disease or remembering it — accepting the lessons from it become vital to preserving the future.

“We must absolutely be prepared for another global pandemic in our lifetime,” Mattison said. “I know I’m much older than you, but I’ve experienced or seen the impact of multiple infectious disease epidemics and pandemics in my life: 1958 influenza, Zika, SARS, MERS, AIDS, measles, Ebola. We must always be ready for the next pandemic.”