HBO’s “I May Destroy You” is an unflinchingly raw examination of the ambiguity involved in consent, addiction and identity. Impressively evading any hint of a sophomore slump, showrunner Michaela Coel — previously known for Netflix’s “Chewing Gum” — has created a masterful portrait of millennial culture in the vein of Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag.

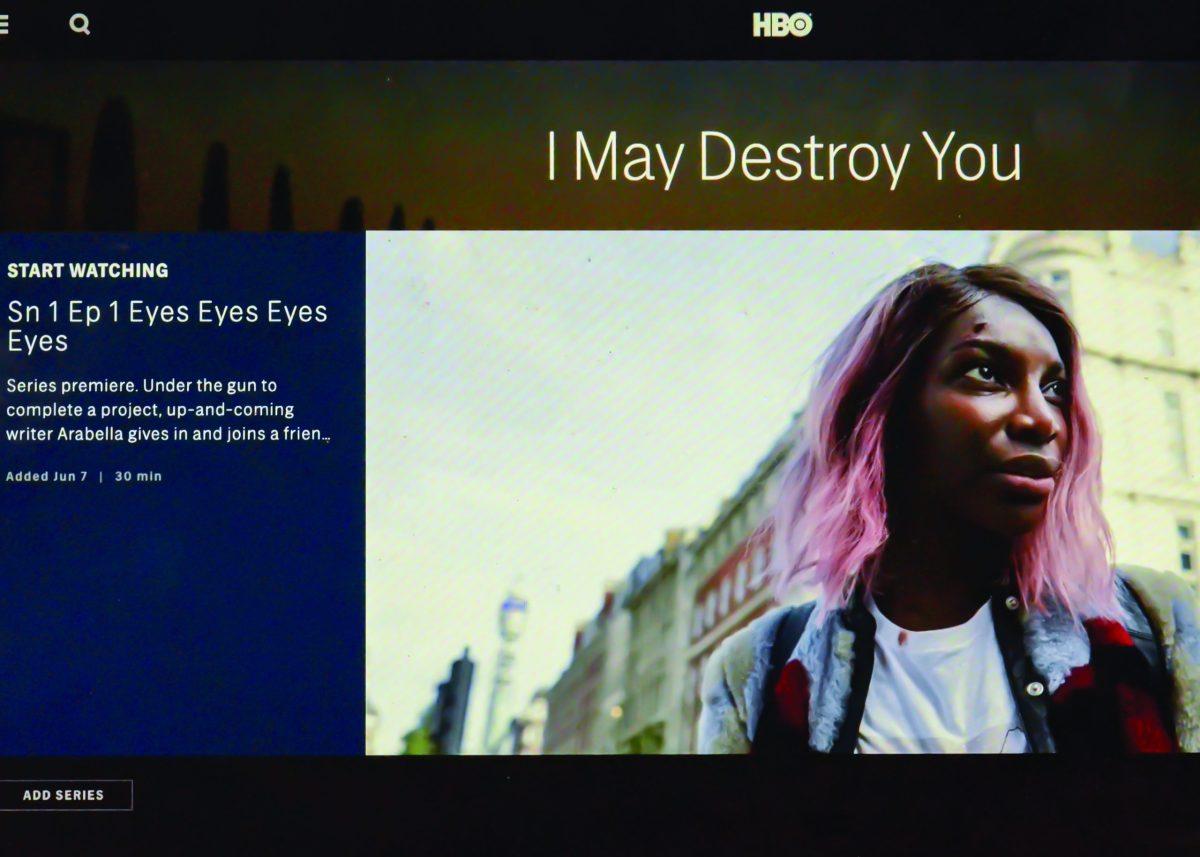

The series follows Coel as Arabella Essiedu, a 20-something novelist with one surprise hit trying to churn out a second, equally compelling book. After her drink is spiked during a night out with friends, Arabella is raped by a stranger, bringing her life and manuscript to a screeching halt.

For better or worse, survivors of sexual assault may see their own experiences sharply reflected in Arabella’s journey–the series was inspired by Coel’s personal experience being drugged and assaulted during the production of “Chewing Gum.”

“Like any other experience I’ve found traumatic, it’s been therapeutic to write about it, and actively twist a narrative of pain into one of hope, and even humor,” Coel said during a speech at the Edinburgh TV Festival in 2018.

Missteps in sexual consent happen in a variety of contexts throughout the twelve episode series. Coel presents these scenarios with deft complexity, touching on several issues not typically seen on television. Stealthing (the unannounced removal of a condom during a sexual encounter already in progress), sexual violence between men and the secret recording of consensual encounters are all featured in storylines that feel unique and authentic. Where exactly the line was crossed is often unclear, leaving viewers with many questions but few answers in a way that feels remarkably true to life.

Arabella’s penchant for addiction becomes apparent very early on. After a friend invites her to come out to a bar with mere hours left before she must submit a completed draft of her unfinished manuscript, Arabella decides to play chicken with her 10 a.m. deadline. She sets her phone’s timer for one hour in an attempt to limit her time socializing, but as the drinks stack up while the bar montage plays on it becomes clear to viewers that Arabella was out much longer than planned.

Ingestible substances are not the only addictions we see characters struggle with in “I May Destroy You.” Arabella’s compulsive use of social media has distanced her from best friends Terri and Kwame, if only she would look up from Instagram long enough to notice. Kwame has his own issues. He is deeply entrenched in Grindr culture, engaging in random hookups with nearby strangers found on the app so frequently that he becomes deeply uncomfortable when one of his would-be hookups suggests they simply share a meal.

Arabella’s emotional journey plays out visually through her ever-changing hair. When we first meet her she’s sporting neon pink, shoulder-length locks. Midway through the series, we watch Arabella do something many of us also do in times of crisis — an extreme hair change. She shaves her head in what could be interpreted as a symbolic attempt to shed her demons (most of which, we later discover, are hidden beneath her bed).

Coel functions as a triple threat in the production of the series — the writer and star also codirected eight of the twelve episodes with Sam Miller. The episodes themselves play out non-linearly. This structure serves the story well, taking us back and forth throughout Arabella’s history and showing us poignant moments from her childhood, teenage years, and the months leading up to the assault. These time jumps flow beautifully; framing Arabella’s present experiences supplements our understanding of who she is and why she does what she does, allowing the audience to sympathize deeply while still holding her behavior up for critique.

Arabella Essiedu is neither hero nor antihero. She is something else entirely, living in a gray area just like the one we spend our own lives in. In a world where much is curated to look idealistic, there is comfort in watching someone else struggle and overcome. “I May Destroy You,” streaming now on HBO Max, is a true work of art and a veracious depiction of life — jagged edges and all.