The story of the man admitted to Drake, the United States, the Army and now the office of admissions: but not in that order.

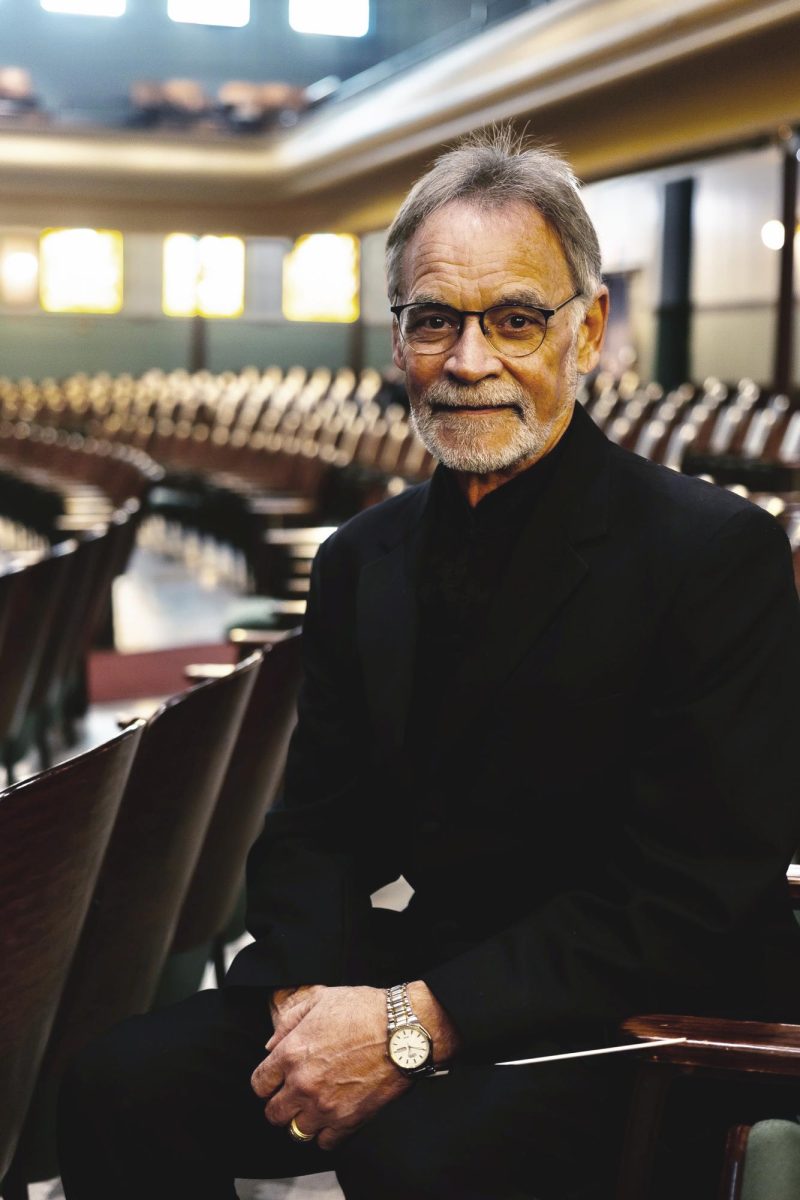

On any given day on Drake University’s campus, the assistant director of admission will walk down the stairs inside Cole Hall with a prospective student and his parents. The assistant director towers over the small family, and his initial appearance is rough and gruff. He seems to try and diminish his size to meet his guests on their level. At the bottom of the stairs, he sticks his hand out and shakes those of the family, a wide smile spreading across his face.

Amir Busnov is this towering figure. His closest friends describe him as a “great, big, bear of a guy.”

“But as soon as he smiles, he puts people at ease,” said David Skidmore, who taught Busnov many years ago when he attended Drake as an undergrad.

And while Busnov tries to diminish his size, he can’t diminish his personality.

“He’s kind of larger than life,” said Graham Gillette, one of Busnov’s closest friends. “He’s such a powerful force.”

Beyond his appearance, Busnov has been described as a “patriot,” a “hero,” and ultimately as the “all-American story.”

But Busnov uses a much humbler word to describe himself, one he’s championed and made his own. Refugee.

“I carried civilians that had been blown into pieces from machine shell.”

Busnov was born over 5,000 miles away from Drake, in a small village in Bosnia called Srebrenica.

“It was pretty quiet, tranquil,” Busnov said of his former home.

Busnov grew up with a communist government, which spread a belief in brotherhood and unity.

“We were raised to believe that everything is nice and dandy,” he said. “We are all equal, that we love each other, that we would never let anyone conquer us or divide us.”

Unfortunately for Busnov and the over four million people living in Bosnia, that changed when the communist party fell apart.

“People didn’t have nothing they could rely on,” Busnov said. “There was nothing else they could organize around other than ethnicity and religious groups. And that’s what it did. As soon as they did that in ’91, hell broke loose.”

The BBC reported that divisions arose between the three main ethnic groups in Bosnia: Serbs, Bosnian Muslims and Croats. The Serbs and Croats wanted to unite with ethnically similar countries, while the Bosnian Muslims wanted to become an independent country.

Shortly after the fighting started, turbulence came to Srebrenica.

“(Srebrenica) was basically destroyed, burned to the ground, in the early months of the war,” Busnov said. “So my family, and myself included, escaped to another town.”

Busnov was already working as a police officer in Kladanj, the town about 40 miles away from his destructed home. However, he and his family couldn’t escape the artillery fire.

“Everybody was fighting on a daily basis,” Busnov said. “I carried on multiple occasions civilians that had been blown into pieces from machine shell.”

Soon, Busnov’s family realized they had to move on and the United States became their destination. Busnov said he had always wanted to move to America.

“I don’t know for what reason, my entire life, even when I was growing up in Bosnia, I knew I was going to end up in the United States,” he said. “But I never believed it was possible.”

It was possible, but it took several years for Busnov’s entire family to move to the States. They first moved to Croatia to wait for their U.S. resettlement applications to be approved. His brother arrived first in 1998. His parents and two sisters followed a year later.

Busnov didn’t join his family until 2000. He said it was pretty awkward being the last one to go, but going back to Bosnia wasn’t an option.

“If we had gone back to Bosnia, we would have been refugees living out of somebody’s basement, working for probably a piece of bread a day,” he said.

“That was the first time I had seen my whole family, all in one place, since April of ’92,” he said. “A lot of tears. A lot of happiness.”

“He’s an American now.”

Busnov soon joined the National Guard.

“It’s something I always wanted to do,” he said.

He was deployed three times. He was an enlisted soldier in Kosovo in 2003, worked as an analyst in Iraq in 2011 and in Afghanistan in 2012.

By joining the National Guard, Busnov was able to become a citizen.

He explains that a friend he met in basic training told him he could get his citizenship without getting a green card first, that a Bush-era executive order allowed active duty members to become citizens.

Busnov recalled going to get his citizenship in Omaha, Nebraska in 2002.

“I was in Omaha, wearing my uniform. I was talking to a lady, reading a list of questions. ‘Are you ready to bear arms?’ And I said, ‘Are you serious?” And she said, “I’m sorry, we have to ask.’”

Busnov’s patriotism is obvious whether or not he’s wearing his uniform.

“It’s his adopted country, and he’s putting his life on the line,” said Jim Spooner, who has known Busnov for nearly 20 years. “That’s pretty heavy stuff. And he’s doing it with a source of pride that I think some of us that are less appreciative of what we’ve got could take note of.”

Spooner further explains that military personnel are sometimes able to take home a flag flown at their base and Busnov was lucky enough to bring one home. But he didn’t keep it for himself.

“(He) gave it to my family for helping to take care of his wife and family,” Spooner said. “That’s not something you really want to give up when you’re dedicated to the flag, but he did.”

“He made it look easy.”

Even though the National Guard became a major part of his life, Busnov had some things to get used to living in America. His close friends said he made it look easy.

“He’s kind of unstoppable,” Gillette said. “I don’t want to minimize how hard it was for the Busnovs to come to a new country, but when he sets his mind to something, he doesn’t let up.”

In Bosnia, Busnov said he learned about American culture from old Western movies and from foreign peacekeepers. This helped set him up for success once he moved to Des Moines.

“Usually when refugees come over, they have that culture shock because everything is so different,” Busnov said. “I already know how they sort of think.”

He said the one thing he could never really get used to was the food.

“There’s things that you like to eat,” he said. “Culturally, (Bosnians) eat stuff at home, everybody cooks. But you have no places where you are so used to it to go out and have anything.”

Busnov’s favorite Bosnian food is burek, and his mother “is probably the best burek maker between Mississippi and Missouri.”

“He’s such a hungry learner.”

After settling his family into Des Moines and in between deployments, Busnov could be found at work or in a classroom.

“I wanted to study international relations,” Busnov said. “I was dead bent on studying international relations. I thought I’d see the world with it.”

He first attended DMACC to take some general education classes.

“Here’s a guy that speaks four different languages, he’s been around the world, he’s fought for his country, and he has to start right at entry level to make this stuff happen,” Spooner said.

Busnov attended classes during the day and worked at night as a security guard at Prairie Meadows to support his family.

“There’s nothing beneath him because he’s a hard worker,” said Lynn Harper, another long-time friend of Busnov’s.

After DMACC, all signs pointed to Drake.

“Somebody I talked to said, ‘Drake’s your best bet,’” Busnov recalls.

He was accepted to the international relations program at Drake in 2005.

“We all wanted him to be successful,” said Eleanor Zeff, one of Busnov’s professors. “We felt he should have every opportunity he could and he was willing to take advantage of it.”

Even though Busnov was at Drake to further his education, numerous professors said he taught others almost as much as they taught him.

“He brought so much into the classroom because he was older and had these extraordinary experiences,” said David Skidmore, another one of Busnov’s former professors. “He just brought a maturity of perspective and personal experience to the classroom that really helped the rest of us think more deeply about the issues we were discussing.”

“He was a very patient and an open person who listened to students, took their perspectives seriously and remained open to dialogue even when things were sometimes difficult for him to talk about,” said Debra DeLaet, another international relations professor.

While Busnov flourished in many aspects of his education, Zeff said one thing Busnov struggled with was writing.

“English was his second language. He was doing higher level work than what his papers would come out as. Obviously, his thinking was much more mature about issues and he was more involved in them, but then he couldn’t quite express it in writing as much as he wanted to,” Zeff said.

Throughout his time at Drake, however, his writing improved.

“I worked really closely with him on a lot of these things and he got better and better and better,” DeLaet said. “And one thing I really appreciated is he sought out the help and was very patient in trying to work on those things because he did want to express himself as well as he could in writing.”

Busnov ended up graduating from Drake in 2007 at the top of his class, receiving the Elsworth P. Woods Prize for being an outstanding international relations student.

After graduating in 2007, his education didn’t stop.

“So he decides to gets a masters,” Spooner said. “So he’s got to get into the executive MBA program in international relations. He got admitted to four out of the top five (programs).”

The program Busnov ended up a part of was the Tufts University Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

“All based on not who he knows but what he knows,” Spooner said. “He (went to a school) with career diplomats and high profile executive business people and Amir, he did it all by strapping on the backpack and lacing up his boots. I was already proud of him for that because he showed his real colors there in terms of being among the elite.”

“Iowa Nice is not just an empty phrase.”

After finishing up school, Busnov and his family moved to California for a short time. However, Des Moines was on his mind.

“I’m attached to this place probably more than any other place,” Busnov said. “This is probably the most welcoming place I’ve ever been in the whole world. Iowa Nice is not just an empty phrase.”

After moving back to Des Moines and officially retiring from the military, Busnov was looking for something he could do for the rest of his life.

“I called him and said you need to think about this,” Gillette recalled sending Busnov an opening in the admission office at Drake.

That’s how Busnov became the assistant director of admission. He now travels to high schools and college fairs, telling prospective students about Drake.

“I don’t have to sell them anything,” he said. “I tell them my experience. Talking to students is the best part of the job for me.”

When he’s not spreading the word about Drake, Busnov spreads the word about immigrants, refugees and Muslims.

“Des Moines is very lucky to have him,” Harper said. “I think of him kind of as an ambassador in Des Moines because so many people know him.”

Busnov wrote an opinion entitled “Terrorists are driven by hate, not Islam” for The Des Moines Register two years ago.

“That took a lot of courage,” Harper said. “In the one he wrote about Islam, it got some good reaction. But there are also some who criticized him or criticized his view. So, I think it takes a lot of courage to stand up.”

His friends say Busnov is all-American even though his story didn’t start here.

“The reason I like talking about Amir is … he wasn’t like you and I, born in the United States,” Spooner said. “He came to us not by accident of birth but by delivery of choice. He’s certainly given me an appreciation for the struggles of people coming to the United States. It’s made me a lot more proud to know him.”

And while many say he’s a success story, Busnov and those who know him know refugees looking to come to America are facing steep challenges.

Busnov speculates that President Trump’s attempts at travels bans on majority Muslim countries, had they been in place 20 years ago, would have kept someone like him from coming to the States.

“What he’s trying to do is not what this country’s about,” Busnov said. “They’re trying to rewind everything that was accomplished for the last 60 years.”

Those who have met Busnov find it difficult to imagine their lives without him.

“Amir humanizes these issues,” DeLaet said. “The word refugee, I think sometimes people think it evokes sympathy, sometimes it evokes pity. But too often it doesn’t evoke a sense of a real human being. So Amir appear puts a real human face on these issues.”

“We need to see refugees and hear the stories of refugees who have been success stories like Amir because there are so many other people who are talking about the negative aspects of refugee resettlement,” Harper said. “People need to be reminded of that.”

“Things will get taken care of.”

It’s been nearly two decades since Busnov left Bosnia and started his new life in Des Moines. While he’s had a strong impact on those who have met him here, he said that getting older makes “you kind of miss the opposite things.”

“(I miss) the relaxed atmosphere back in Bosnia,” he said. “Nobody’s in a hurry. You don’t worry about it. Things will get taken care of.”

Busnov said working at Drake is something he could do for the rest of his life. His friends say he could be a teacher or even an ambassador someday. But whatever he ends up doing, he’ll continue sharing his story and leaving them with a positive impression of what it means to be a refugee.