In 1887, the man who may have been Drake’s first Black student graduated from the Drake Bible College, which later became Drake University. Born in 1859 in Kentucky, Simon W. Scott would have been in his mid-to-late 20s at the time of graduation.

Throughout his time at Drake, Scott lived with a professor. On June 13, 1886, he recited “Uses of the Ocean” to the Berean Society, a literary organization that no longer exists at Drake. Beyond this, little else is known about his college experience.

“This is one example of many stories that haven’t been told fully, or there’s more to the story than what we know,” said Hope Bibens, director of Drake University’s Archives and Special Collection.

Drake archivists had assumed that Scott was the first Black student for decades. Bibens had heard of him in her first year at Drake, at least.

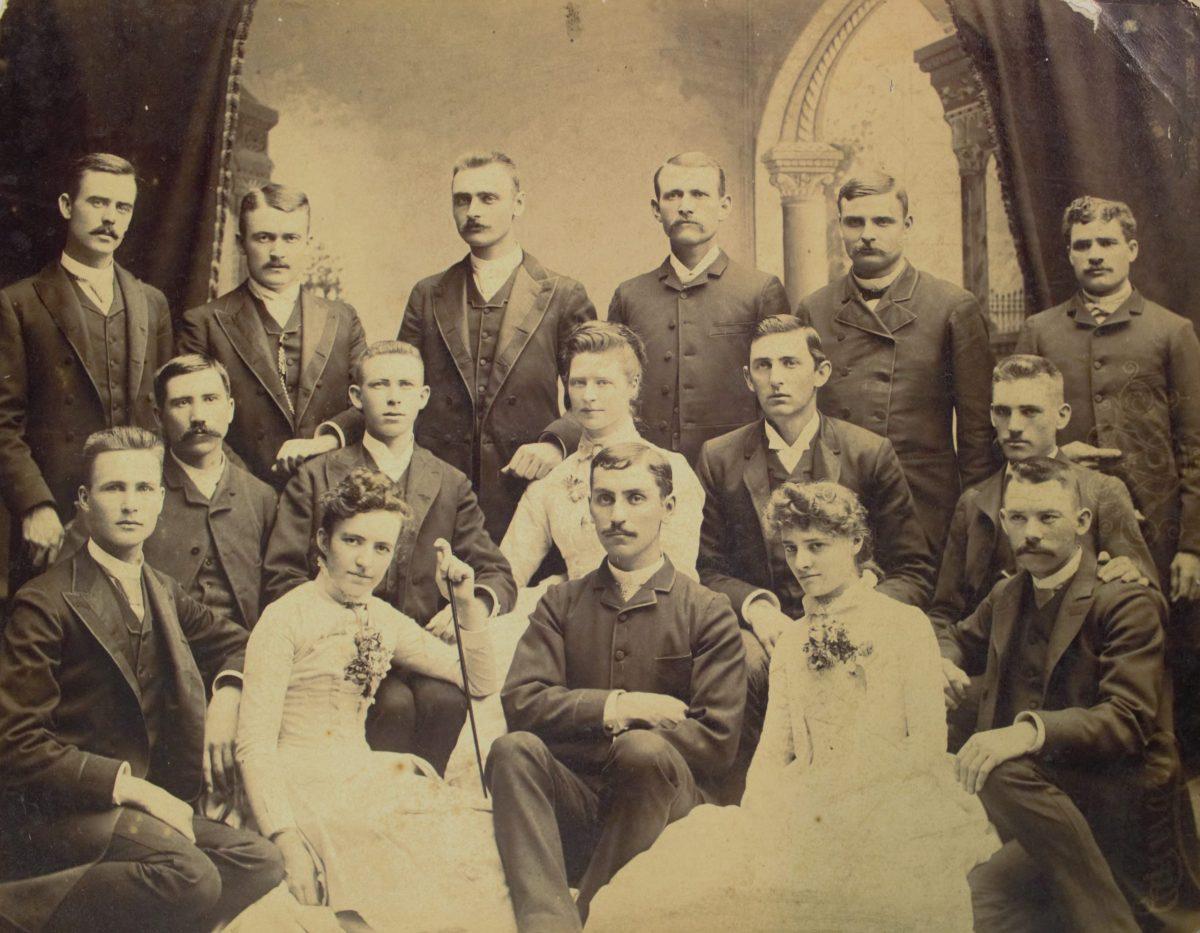

In one of the only known photographs of Scott at Drake, an unknown person wrote “n***o” beside his name. While it is unclear why his race was recorded in the photo, there is more evidence to show that Scott was not White.

After graduating, Scott ministered for the Disciples of Christ Church, which Drake Bible College was affiliated with. The Disciples of Christ kept yearbooks that included lists of all ministers and their locations. United States census records show a “Simon W. Scott” in the same locations where the church records show Drake graduate Scott. In the census, Scott was recorded on the census as “n***o.”

“For census purposes, the term ‘Black’ (B) includes all persons who are evidently full blooded n***o, while the term ‘mulatto’ (Mu) includes all other persons having some proportion or perceptible trace of n***o blood,” reads the 1910 United States census definition for race.

The census in 1900 shows that Scott was in Greenville, Texas as a minister, and sometime thereafter moved to Kansas City, Kansas, where the census recorded him in 1910. While there he taught high school; it is unclear if he was still ministering at the time.

The archives has been reaching out to the Disciples of Christ and other parties for more information.

“We don’t have a whole lot [of information] here, in our collections. We have to branch out,” Bibens said. “It’s almost like genealogy research, what we’ve been doing to find out more about him.”

To find out as much as possible, the archivists are tracking both his descendants and ancestors. But this genealogy comes with difficulties, as Scott’s parents are unknown.

“One of the things about him that makes it difficult is that a lot of times students would list their parents, but because he was older when he enrolled at Drake, he wouldn’t have,” Bibens said.

There are specific difficulties in tracing Black Americans’ family trees. The main difficulty for Scott’s genealogical tree is the lack of known parental names, but even with names, it could still be difficult. If any of Scott’s ancestors were enslaved, which is unknown, there are also specific challenges that come with that.

The University of Kentucky’s Notable Kentucky African Americans database lists the difficulties of record-searching for formerly enslaved people in Kentucky, including the lack of a state-wide list, name changes or only first names on record. Slavery would not end in Kentucky until the ratification of the 13th amendment, six years after Scott was born.

However, it is not known if either of Scott’s parents were slaves. According to the University of Louisville, the city of Louisville, Kentucky, had the largest free Black concentration in the upper south (west of Baltimore). But even if they were free, tracking them is difficult without knowing either of their names.

“This type of research, you run up against a lot of dead ends, you have to find other trails to follow,” Bibens said.

A student at Drake cast doubt on Scott’s racial identity. Eunice Hubbell, who was in his graduating class, spoke at an event called Class Day in 1887. While it is unclear what she specifically talked about, as it wasn’t recorded, attendees at the event said she implied that Scott was, in fact, white. The archives are unclear on why she brought this up, but her allegations are the only counter-evidence to Scott’s racial identity.

“All of the other facts we have outweigh whatever doubt she might have cast,” archives associate Benedict Chatelain said.

Scott did not attend Drake during a census year, where he may have been recorded as being in Des Moines. In fact, Drake had not yet seen a census year, as it had been founded in 1881.

Drake’s articles of incorporation, its oldest governing documents, state that: “All the departments of this university shall be open alike for both sexes and for those of any religion or race. Whether that was put into practice from the start is unclear.

There is also no way to know for sure except by tracking the census records of every Drake student. Drake’s dorms would not be officially integrated until 1946.

“We can’t know his experiences here. He didn’t live in the student homes with the other students. It could’ve been because he was older, but also there wasn’t enough room in the students’ homes for all the students and it wasn’t uncommon for students to live in the neighborhood,” Chatelain said.

Scott died in 1922. Census records show that he married a woman named Lena. Scott is buried in Kansas City, Kansas.

Bibens said that there are many stories like Scott’s that could be told through archival research.

“I encourage Drake students, if they have research projects they’re working on, we’ve got a ton of stories that haven’t been told completely,” Bibens said.