Run like hell: a mixed bag of evidence concerning athletes’ mental health

Photo Courtesy of Canva

Photo Courtesy of Canva

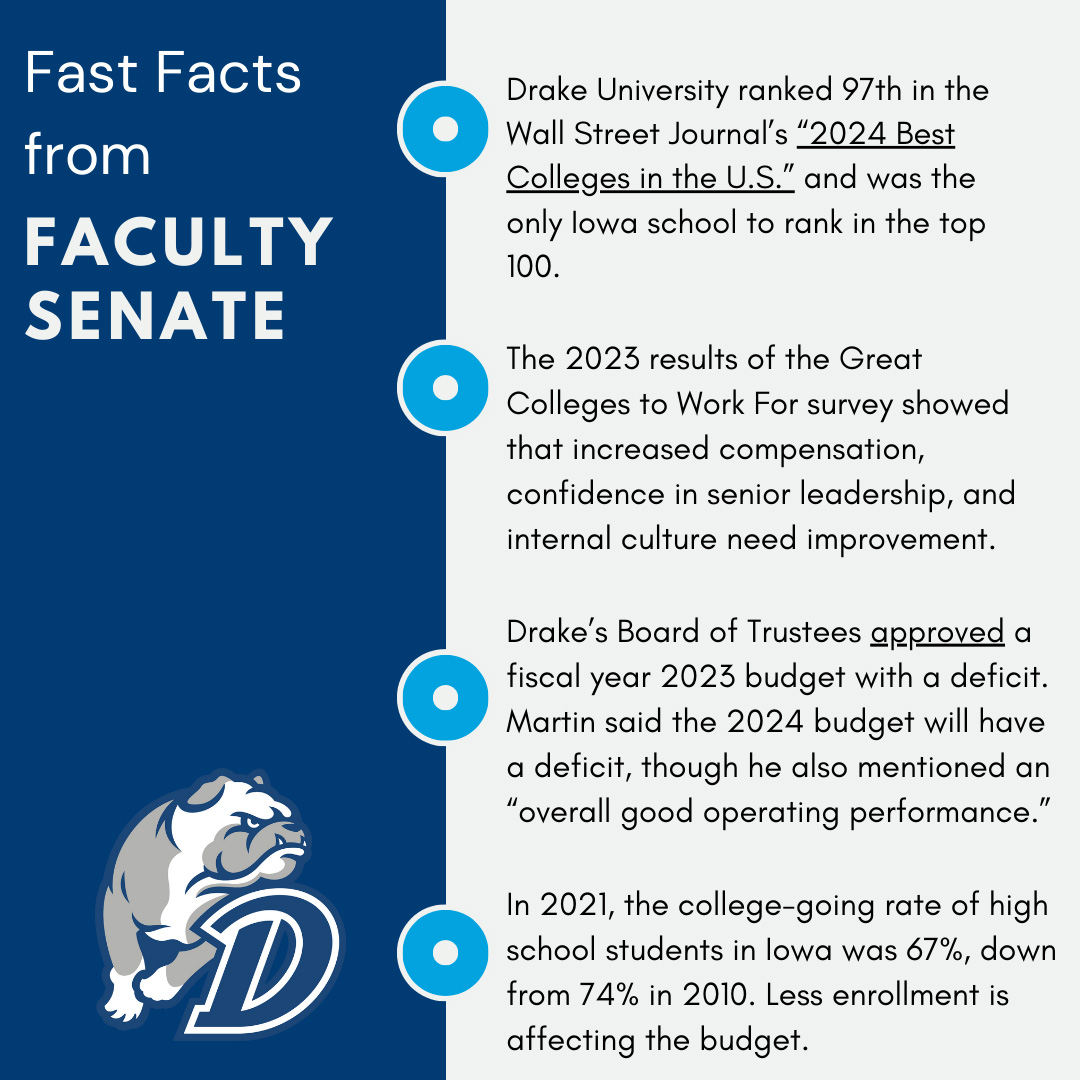

The mental health of athletes is becoming an increasingly talked about topic in the sports medicine community, especially because their profession makes them more vulnerable to stressors like excessive competition.

A 2020 article published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine found that high athletic identity is associated with both positive and negative health and performance outcomes. Psychological and sociocultural factors have been raised as potential risk factors for injury. Stress repeatedly displays a relationship with injury risk as well as the capacity to recover from injury and resume sport, making cognitive, emotional and behavioral reactions to injury significant in deciding outcomes.

They also found that college student-athletes report depression symptoms at a higher prevalence than previously reported. A 2016 article published in that same journal showed that female athletes had a greater incidence of clinically significant depressive symptoms, indicating that female collegiate athletes may be more susceptible to depression than their male colleagues. Female track and field athletes had the highest prevalence of depressive symptoms, whereas male lacrosse players had the lowest prevalence.

While some studies found a positive association between higher self-identified runners, low levels of depression and high self-efficacy, others suggested that running did not directly impact stress, according to a 2020 article published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health that reviewed the literature on the relationship between running and mental health from the past 30 years, gathering data from over a hundred papers.

Long-distance runners’ questionnaires revealed a relationship between long-distance running and disordered eating habits, with obligatory runners–obsessive runners who put relationships and commitments on hold for running and experienced withdrawal symptoms if they missed a run – exhibited traits typical of anorexia nervosa (an eating disorder that results in extreme restriction of calorie intake). Female obligatory runners were most at risk of eating pathophysiology. Male high school cross-country runners were also found to have risk factors for eating disorders.

Further, non-elite marathon runners had much greater exercise dependency scores than for-leisure runners who did not run marathons, but they also had more self-sufficient personalities. This was supplemented by the findings of a 1991 study, which showed that pain runners – those who push themselves to the point of agony – experience considerably more death dread and death anxiety on the Dickstein Death Concern Scale than non-pain runners. Additionally, when habitual runners were unable to run due to illness or injury, they had much more overall psychological distress, depression and mood disruption, as well as significantly worse self-esteem and body image than those who continued to run.

That being said, studies have also shown strong positive correlations, with findings indicating that acute bouts of running might benefit mental health and that different types of running can have varying impacts. According to the research, acute bursts of running on a treadmill, track, outdoors or in a group setting (2.5–20 km, 10–60 min) all enhance mental health outcomes. When compared to non-runners, there is strong evidence that regular or long-term recreational running is associated with better mental health results. As opposed to levels of moderate running, there was evidence that high or severe levels of running (high frequency and long distances, including marathon running), were linked to indicators of ill mental health.

When looking at longer-term interventions, the studies generally revealed improved indicators of a variety of mental health outcomes, including results in psychiatric and homeless populations when compared to non-running controls. However, longer-term running interventions’ potential impact on detrimental mental health consequences is yet uncertain.

The review concluded that while there were variations in outcomes and certain groups were more vulnerable to risks, there were overall similar beneficial trends and positive implications, especially for depression and anxiety disorders. The demographics of the participants in the studies reviewed, however, were not very diverse. Additionally, the small number of studies that included controls or comparisons hampered attribution. It was also difficult to synthesize quantitative impacts since reporting methods of the reviewed papers varied widely.

They also discovered a more limited evidence base that was concentrated on clinical groups. In populations with clinical depressive disorders, behavior change and compliance can be difficult, and there is less research on the long-term benefits of physical exercise in the treatment of depression.

Further studies are required to fill these knowledge gaps with particular effort in diversifying the sample size, especially for certain groups like runners under the age of 18, over the age of 50 and clinical populations. To improve the recommendations for running and mental health, a comparison of the different running styles, environments and intensities is required.

We need more research to study the overall relationship between running and mental health with a diverse demographic and large sample size that is not limited to collegiate athletes for a stronger positive implication that could potentially help as a treatment for anxiety disorders and depression for the general public. Studies that focus on more average, moderate runners is a necessity for this as most studies prefer young professional track athletes or amateur marathon runners as their subjects.

Further concentrated research is also essential for groups such as female track and field athletes, obligatory long-distance runners, male high school cross country runners and pain runners as they are more vulnerable to anxiety disorders, depression or eating disorders according to existing literature. Researching better treatment options and creating strong built-in support systems could benefit these individuals tremendously.

Competitions and showcase events can heighten these issues and make them worse, so if you are going through something similar or know someone going through something similar, please know that there are resources available that can help if you’re willing to reach out.